A “Multi-Tasking Mobility Machine” that Baffles the “Experts”

Note: This article was originally published August 2004. Amtrak no longer makes the data used in this article available to the public. We believe that the basic argument remains sound.

By Fritz Plous

Physicists argue that the bumblebee cannot fly because its body is too heavy and its wings too small. But the bumblebee does not know this, so it flies anyway.

Beware of “experts.” Wherever they look they find another bumblebee.

Take the so-called “passenger train experts.” They claim Amtrak’s Chicago-Seattle Empire Builder shouldn’t work: its route is too long, its speed too slow and its territory too thinly settled to attract today’s travelers.

The Builder doesn’t know this, and so it’s the best performing train west of the Alleganies.

Looking at what the Empire Builder actually does, not what its critics think it does, explains why.

[And offers lessons for a broader network.]

On December 26, 2002 the eastbound Empire Builder left St. Paul, MN headed for Chicago with roughly 500 seats, 350 coach and 150 in private rooms with separate cafe and dining facilities. Additional capacity can be added at marginal cost. The maximum capacity of the newest 747 is 524 seats.

Not your grandfather’s long-distance train

Technically, the critics are right on one point: The Builder starts its run in Chicago, and finishes up in Seattle, 2210 miles and two time zones west after 43 hours and 10 minutes on the road. In that sense it is indeed a “Chicago-Seattle” train.

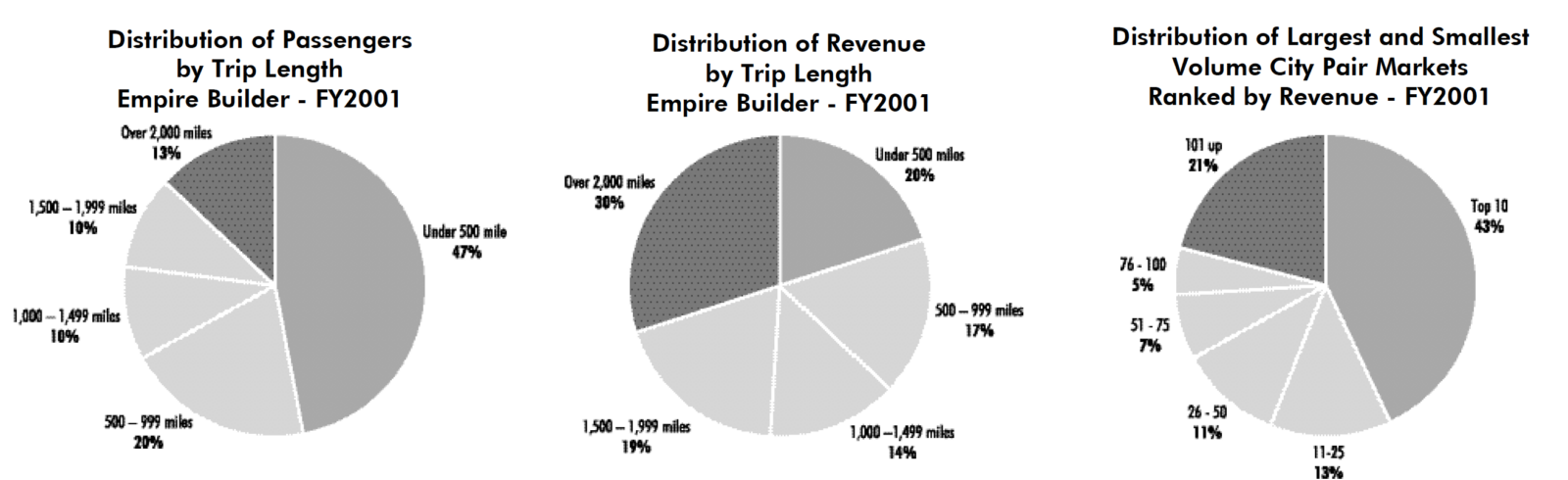

But that’s not the way its patrons use it. Only about 9 per cent of the Builder’s passengers travel the entire distance.

The remaining 91 per cent of the Builder’s passengers are short- or medium- distance travelers. They ride between any and all combinations of Chicago, Seattle and 45 intermediate stations (A smaller section of the train branches off from the main train at Spokane, Wash., and finishes its run in Portland, Ore.).

Count them: 931 trips on one train!

In fact, the permutations of all those stations yield no less than 931 possible city pairs for which Amtrak’s computers can print a ticket good on the Builder.

So it might be better to think of Amtrak’s Empire Builder not as a long-distance train, but as a series of heavily used intercity corridor trains linking places such as Fargo and Spokane, Milwaukee and Glacier National Park, or Winona and Grand Forks.

“And it is heavily used,” says Ray Lang, Amtrak’s director of government affairs in Chicago. “I’ve visited every community the Builder serves and the people up there depend on it—college students, business people, tour groups, overseas visitors who want to see the American West, retirees, families visiting relatives, Native Americans traveling between reservations, tourists and skiers headed for Glacier, patients trying to get to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.”

A Long Route Builds Volume

Several analysts have proposed breaking routes like the Empire Builder into several segments.

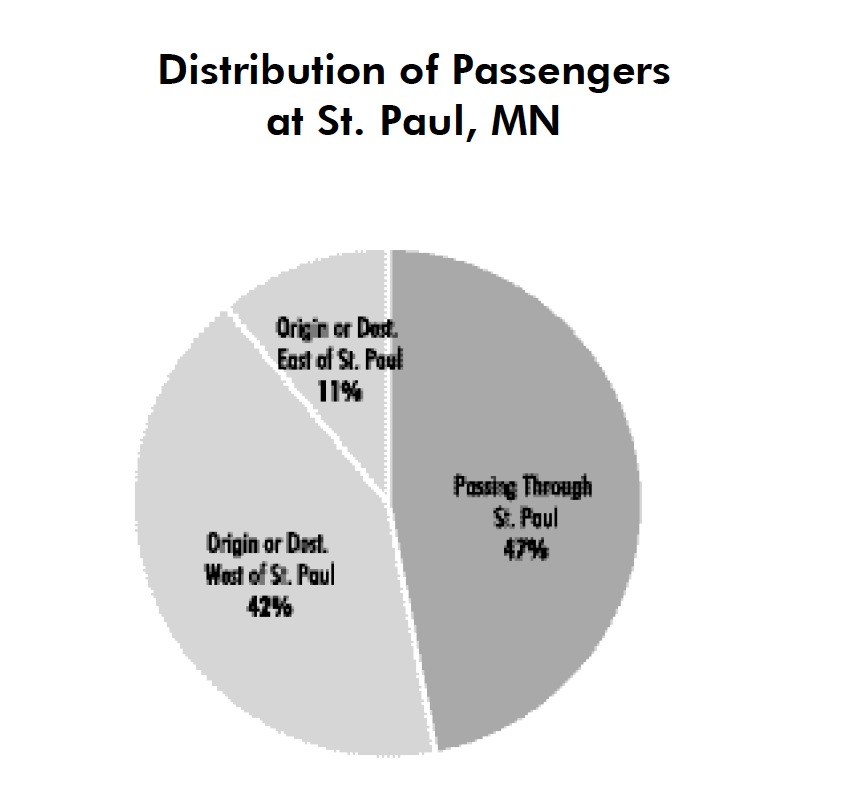

The Empire Builder’s usage at St. Paul demonstrates why this change would be very damaging.

Fully 47% of the passengers who arrive at St. Paul stay on the train. A forced transfer would make the product less attractive to almost half the current customers, reducing revenues. Operating costs would simultaneously increase.

A better plan would be to protect and grow the existing base market on the existing train and add frequencies on discreet segments, such as Chicago to St. Paul.

Nearly half of Empire Builder passengers stay on the train at St. Paul. Forcing them to change trains here would make taking the train less attractive.

The Builder is their lifeline

“There is no other form of transportation up there that links the big cities with the small towns the way the Empire Builder does,” Lang says. “There is very little bus or air service. The Interstate is 100 miles south—all they have is U.S. 2, which is mostly two-lane. The weather upthere is terrible in the winter. Without the train there is no way to get around.

”The average trip length on the Empire Builder is 845 miles, a little more than a third of the train’s total route. Station stops sometimes are long because people get on and off at every stop, even tiny rural points that most interstate tourists ignore.

“The Builder is their lifeline,” Lang says.

First-class few finance many in coach

Interestingly, Builder passengers traveling more than 1,000 miles make up only 23 per cent of the train’s ridership—but they generate 63 per cent of the revenue. The 47 per cent who travel less than 500 miles provide only 20 per cent of the revenue. And sleeping-car passengers, who pay premium fares, provide 43 per cent of the Builder’s revenues, despite making up only 16 per cent of its passenger list.

“That effectively refutes the argument you sometimes hear that Amtrak shouldn’t be operating trains for so-called ‘wealthy leisure travelers,’” says Chicago-based Amtrak Media Relations Manager Marc Magliari.

“The first-class travelers make train travel possible for the coach passengers,” Magliari said. “I’d call that a good deal.”

The airlines use the same economics to keep their coach fares reasonable. But no matter how the data are sliced, no single market segment dominates. The Empire Builder is everybody’s train, gathering and distributing so many varieties of travelers between so many origin- destination pairs that no other transportation resource can match its versatility or efficiency.

The Empire Builder combines multiple trip types and lengths into a single, high-volume vehicle. As a result, the high-revenue sleeper passengers make it possible to provide service to passengers making shorter trips at a more reasonable cost. While the top ten city pairs provide the bulk of passenger volume, trips between smaller cities are too big to ignore.

“A multi-tasking mobility machine”

“I don’t consider the Empire Builder a Chicago-Seattle train,” says Chicago lawyer James E. Coston. “That’s just where its rolling stock originates and terminates. The Builder actually is a multi-tasking mobility machine that serves dozens of markets at once.

”Coston, who worked as an Amtrak ticket and baggage clerk when he was a college student and served on the Amtrak Reform Council from April, 2000, to December, 2003, said the Builder’s logistical efficiencies are not unique.

“All the long-distance trains have similar demographics and economics,” he said. “I used to sell Amtrak tickets and handle baggage at Chicago Union Station, and the customers I served came from everywhere and went everywhere—not just to the end points. The principle is the same whether you’re talking about the Empire Builder or the Southwest Chief or the California Zephyr or the City of New Orleans. The reservations computer showed the vast majority of the riders originated or terminated at intermediate stops that either did not have air service or were very fatiguing to reach by car.”

90 million Americans won’t fly—they need more trains

And there are lots of potential riders still out there, Coston said.“Thirty per cent of Americans surveyed have told pollsters they absolutely will not fly, either out of fear of flying or just plain discouragement with the airline system,” he said. “Plus there’s a large and growing number of people who cannot drive or prefer not to drive. Add them together and you find there is a very large market for short-distance travel on long- distance trains. We need at least one more train on each of those routes.”

Why more service?

“Substantial numbers of people already are boarding the westbound Empire Builder at Fargo at 3:49 a.m.” Coston said, “and there are lots of people boarding the east- bound at 2:10 a.m.

“Can you imagine what kind of business Amtrak would be doing at Fargo if another train went through at a decent hour? The Fargo-Moorhead area has more than 100,000 people. And every Amtrak overnight train has between 5 and 10 stops it serves at an inconvenient time.”

Rolling-stock shortage limits travel

“Amtrak carried 24 million passengers in 2003—up a million over the year before, and so far this year we’re 400,000 passengers ahead of where we were a year ago, which means we’ll add more than a million more passengers this year,” Lang told the Spring Conference of the Midwest High Speed Rail Association in Chicago March 20.

“Basically, all our trains are now running full, because we haven’t got enough rolling stock to accommodate all the people who want to ride,” Lang said. “When David Gunn became CEO two years ago we had 100 damaged cars waiting for rebuilding at our repair shops in Beech Grove, Ind., and Wilmington, Del. Mr. Gunn has got 30 of them back into service, but we still have a long ways to go. Sleeping-car space is particularly hard to get,” Lang said. “On Western trains such as the Builder it’s booked months in advance.”