Our Vision

The Wolverine corridor is densely populated with some of the most dynamic and innovative businesses and institutions in America.

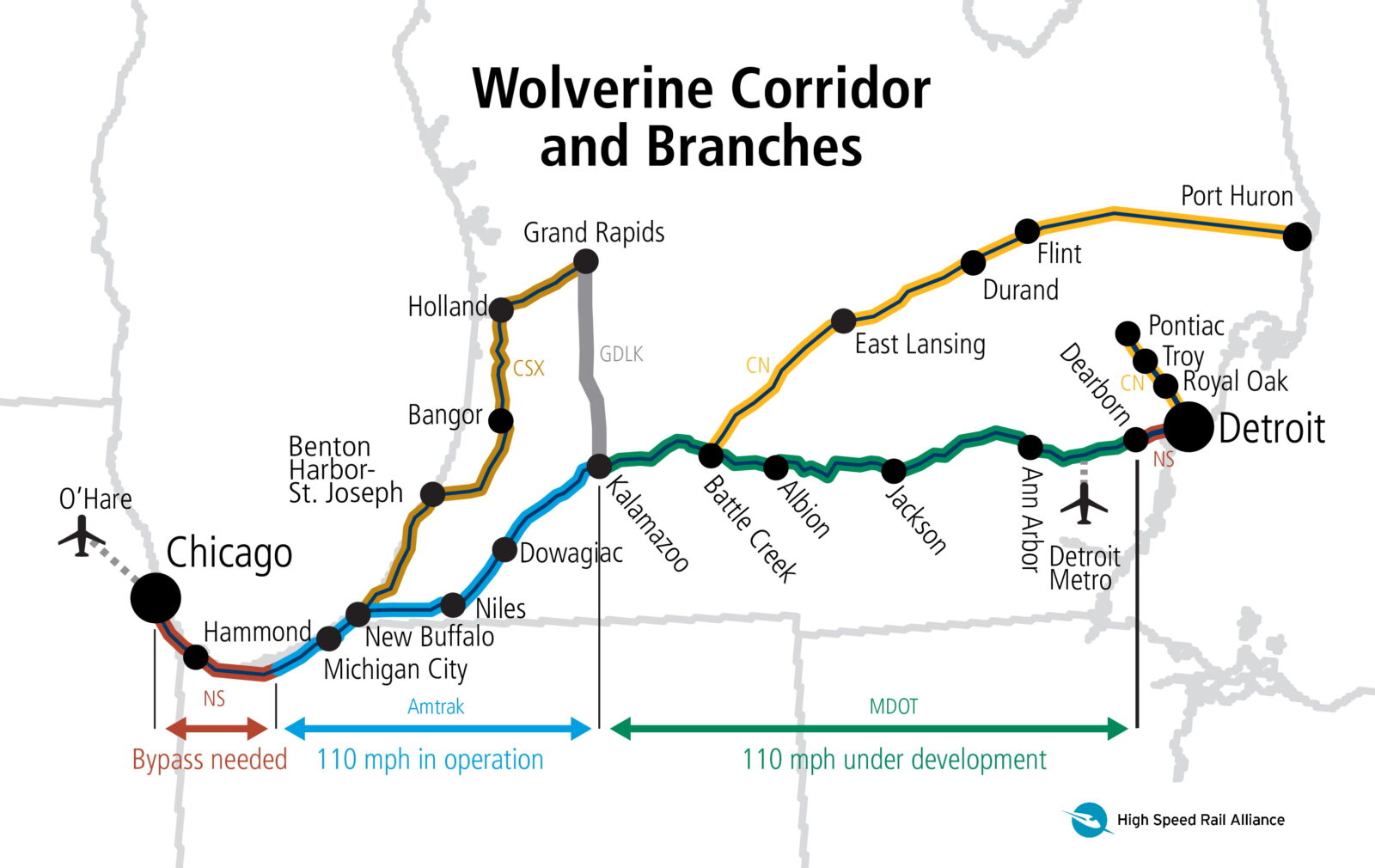

It’s also home to one of the longest segments of publicly owned tracks in the nation. It was the first corridor outside the Northeast Corridor with 110-mph trains.

The Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) is taking slow and steady steps towards modern service.

Expediting the work, with a goal of hourly departures, would create vital links among some of the state’s most vibrant cities.

The Wolverine Corridor is a vibrant economic corridor, with important facilities, such as the Defense Logistics Agency in Battle Creek.

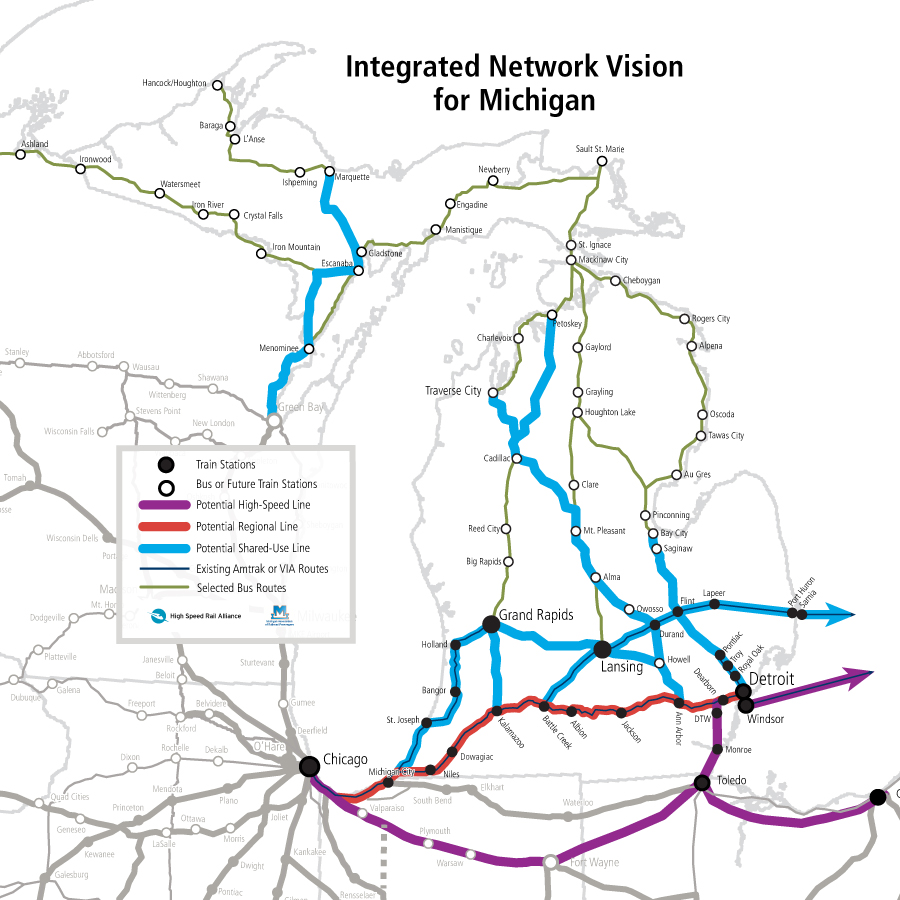

The Chicago – Detroit Wolverine Corridor and its two branches are the foundation for an integrated rail network in Michigan.

Step-by-Step Progress

Illinois, Indiana and Michigan have all made important investments in the corridor over the past decade.

Most importantly, MDOT purchased the segment from Kalamazoo to Dearborn and returned it to 80 mph standards. The previous owner, the Norfolk Southern, had let the track deteriorate causing trains speeds to drop to 30 mph for long stretches. Now, MDOT is realigning curves and testing signals that will allow 110 mph speeds on that stretch.

InDOT worked with the Norfolk Southern to add sidings and other improvements around the southern end of Lake Michigan in a project called “Indiana Gateway.”

IDOT and Metra built the Englewood Flyover in Chicago to eliminate a big delay point.

It is time to capitalize on the recent progress and accelerate it.

The Englewood Flyover on Chicago’s South Side made Michigan’s Amtrak trains more reliable.

Kalamazoo, MI is home to two universities and important pharmaceutical companies.

Top Priority: Add Daily Departures

Now that the corridor is stabilized, the state should maximize its competitive advantage by adding daily roundtrips.

Today, there are only three trains a day from Detroit to Chicago, with an additional trains from Kalamazoo. This simply isn’t enough to properly connect these cities.

Ultimately, the state should build the infrastructure needed to operate hourly, regional rail service. In the meantime, it urgent that the state add additional departures with the infrastructure it has. That would mean Detroit focused trips originating in Michigan City or New Buffalo.

The speed of these trains could also be boosted with “tilting” trainsets, which take curves at faster speeds than conventional trains. (The line is especially curvy east of Battle Creek). That change alone would reduce travel times between Chicago and Detroit by roughly 30 minutes.

Next Steps

There are several improvements that can be made quickly to improve service.

For example, Amtrak is seeking funding to add 16 miles of double track east of Niles.

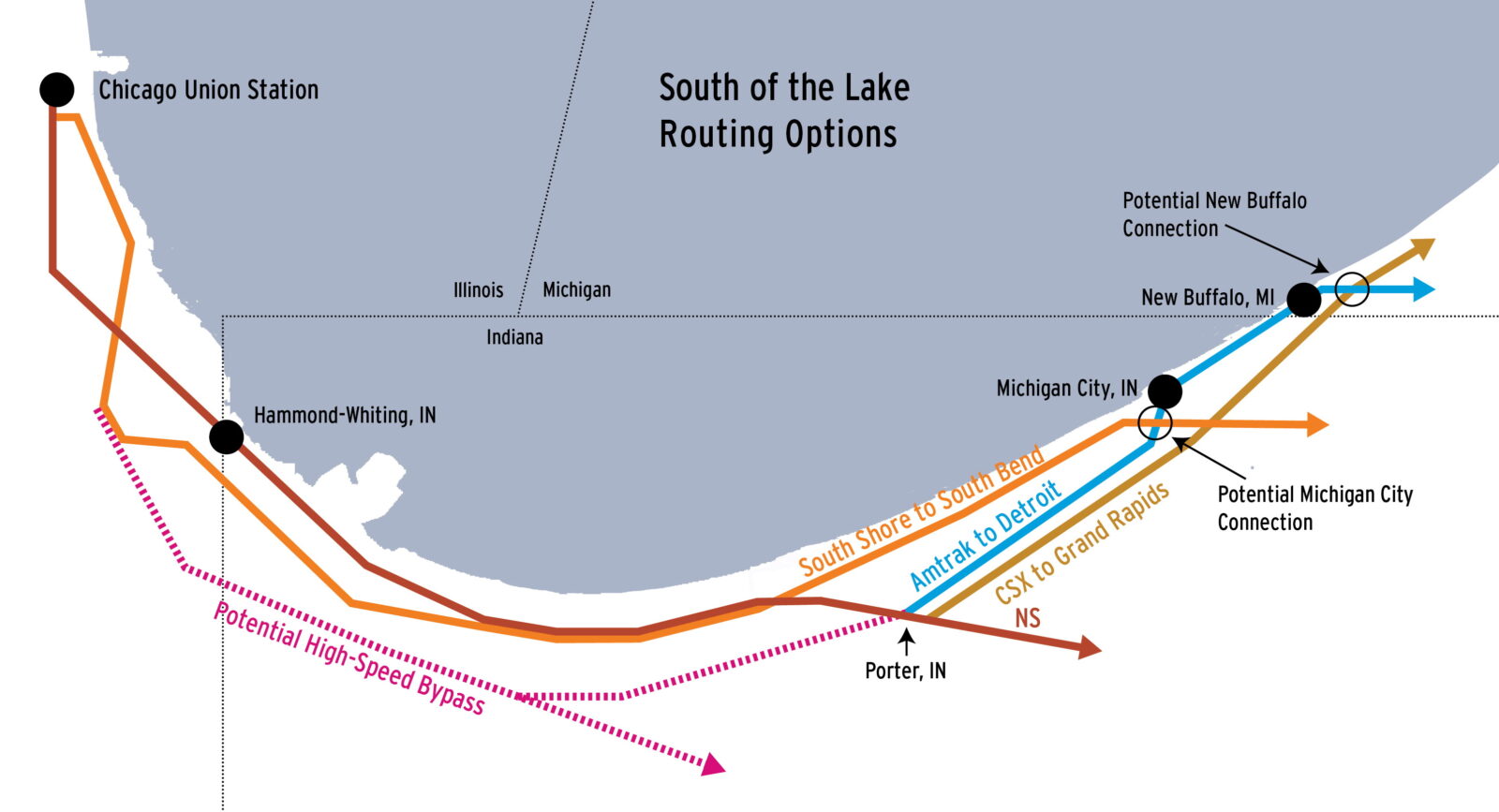

Additionally, a new connection between CSX and Amtrak near the New Buffalo station would allow the Pere Marquette to stop at New Buffalo and Michigan City, making the train much more accessible to residents of southwest Michigan and northern Indiana—and to people transferring from Pere Marquette to Wolverine trains (or vice versa). Currently, there is no transfer point outside of Chicago.

A new connection near New Buffalo would allow the Pere Marquette trains to serve this busy community.

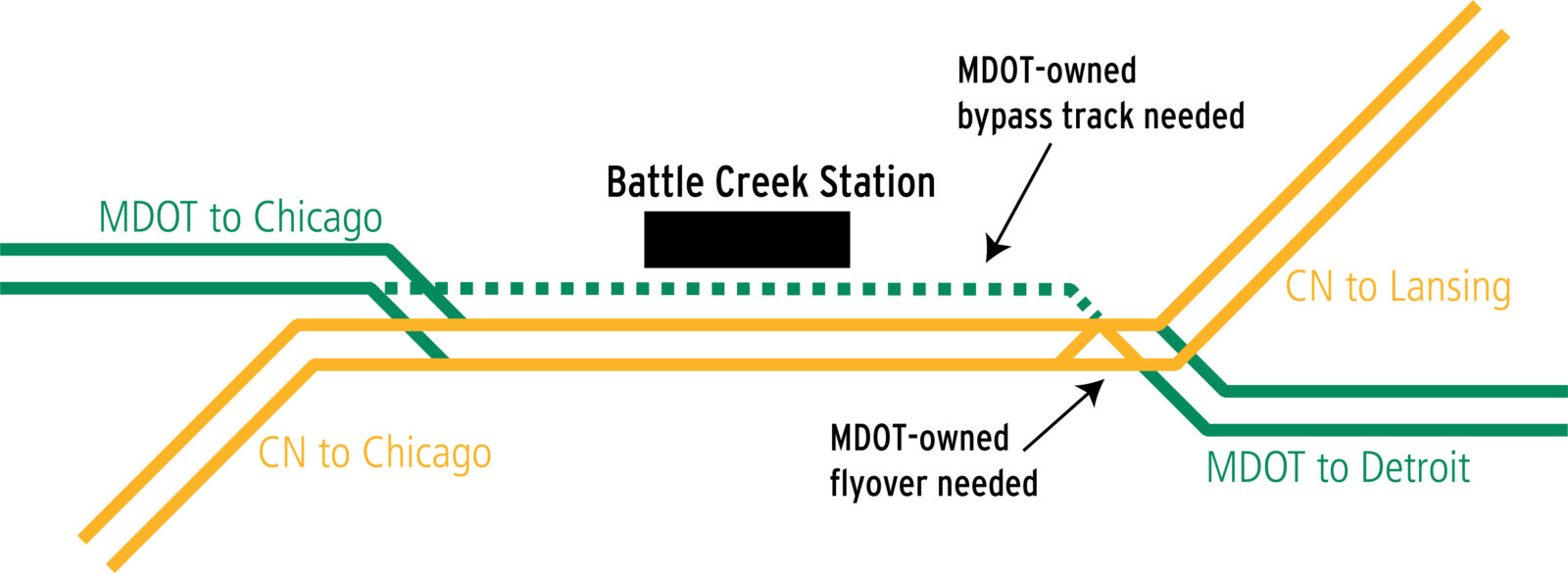

Battle Creek Bypass

There is a short section in Battle Creek where Amtrak shares tracks with the CN. A new, MDOT-owned track is needed to avoid delays to freight and passengers alike. A new bridge to allow this track to flyover the CN would allow for more frequent trains.

MDOT recently received a federal grant to start designing this bypass.

South-of-the-Lake

For the bottleneck south of Chicago, a dedicated, double-track bypass running from Porter, IN to Chicago is the ideal solution. MDOT has already worked on preliminary plans for the project. It should aggressively move forward with those plans.

There is also a workable interim solution: Amtrak could add new daily departures by using the South Shore Line, which is adding a second track to its line from Michigan City to Gary. That upgrade will dramatically increase the capacity for passenger trains and decrease delays on Wolverine trains.

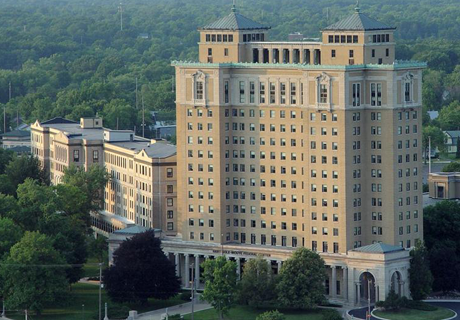

Michigan Central Station

Michigan Central Station, in downtown Detroit, is being renovated by Ford Motor Company to be a center for mobility innovation. It should also become the anchor for the Wolverine, a thriving hub of the state’s revitalized, reimagined railroad network—and a beautiful symbol of Detroit’s rebirth.

Long Term: Hourly Service

Hourly service—with coordinated train and bus schedules—is the ultimate goal.

As it stands, the Wolverine line is of little use to riders who need to make day trips. Attracting more people means offering riders good, same-day options for the trip to their destination and the trip back.

Hourly trains and coordinated schedules make it simple and easy to transfer to other trains and bus lines, going to all parts of the state.

Which means Wolverine trains will be more than just a limited service for people who occasionally need to get to Chicago, Ann Arbor, and Detroit.

They’ll be the first option for riders making all kinds of trips, every day. Commuters, tourists, students, and others will routinely rely on trains to travel all across Michigan—and to Chicago.

Foundation of a statewide network

The Wolverine is just one piece of what should be an aggressive program to link the state with affordable trains and expanded bus lines.

A comprehensive plan is the key to making all of this work: fast trains, frequent service, coordinated schedules, fixed bottlenecks, and a new railroad hub. California is the first to do such a plan, and Michigan should follow their lead.

Please take a moment and let state leaders know: We need a statewide transportation plan that moves us well beyond the same old same old.