How High-Speed Rail Will Reduce Carbon Emissions Getting serious about climate change means getting serious about building great trains. Join Us The best way to cut carbon emissions while expanding our freedom to move Take a look at the numbers below from...

Guest post by F.K. Plous

There’s a great little regional rail corridor just waiting for development in booming Lower Michigan.

Consider the elements that make a passenger-train corridor work: thriving industries, a state capital, two huge universities, a mammoth world-class medical center and teaching hospital and a major tourist attraction. Link them together with just under 200 miles of rebuilt, well-maintained railroad, and you’ve got a recipe for America’s latest passenger-train success. All it takes is the will to fund it and the right people to run it.

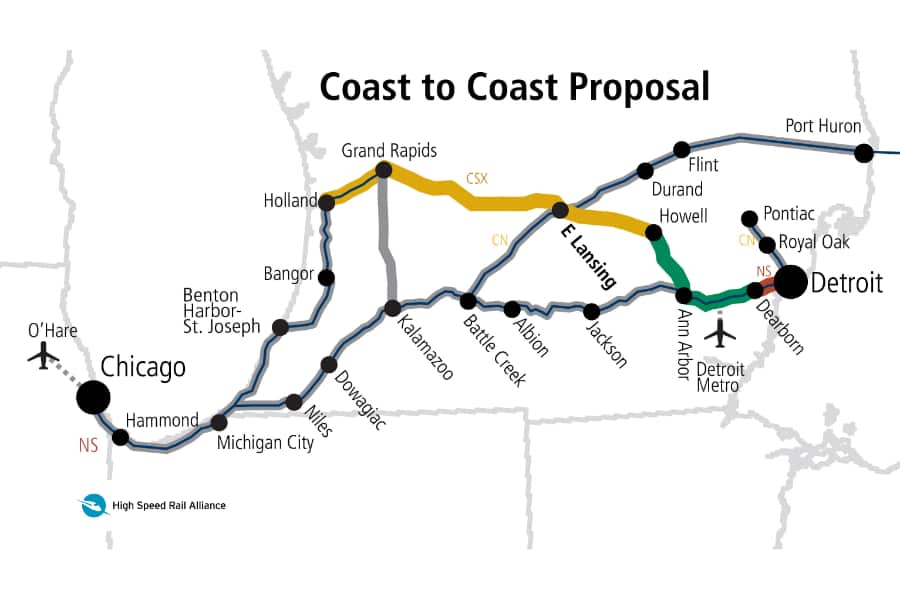

Supporters at the Michigan Environmental Council call it the “Coast to Coast Corridor” because it runs from Holland on Lake Michigan to Detroit on the narrows that joins Lake Huron and Lake Erie.

Coast to Coast supporters are hoping the name—and some encouraging ridership forecasts—will charm the necessary funding out of the Michigan General Assembly and the federal government.

Download the Coast-to-Coast study executive summary

Michigan’s priorities

Michigan is not indifferent to the importance of passenger trains. It’s been sponsoring them for decades, including a single daily Pere Marquette frequency from Chicago to Grand Rapids; another daily run, the Blue Water, from Chicago to Lansing and Port Huron; and the state’s crown jewel, the Wolverine corridor, with three daily round trips between Chicago and Detroit.

Altogether, Michigan and the federal government have invested nearly $2 billion on infrastructure to improve those services, especially the Wolverine and Blue Water, which enjoy long stretches of track that permit 110-mph operation. Public response has been strong. Ridership keeps growing.

But the greatest potential for ridership growth in Michigan may lie with a corridor that never reaches Chicago. A totally intrastate route—the Coast to Coast—embraces an intra-Michigan catchment area with two kinds of powerful numbers: cities with large populations, and populations with a strong preference for train travel.

A virtually ideal route

The Coast to Coast corridor is 177 miles long as originally proposed. That’s the mileage from Holland to Detroit via the former Pere Marquette Railroad, now part of CSX Corp. CSX says if the state offers a fair price for the line the company would consider selling it as long as any upgrade for passenger service included sufficient capacity for freight trains.

Starting from Holland, the Pere Marquette route passes through Grand Rapids, Lansing and the northwest-Detroit suburbs of Howell, Brighton and Plymouth before terminating just north of downtown Detroit at Amtrak’s New Center station.

Pere Marquette never ran through trains all the way from Detroit to Holland, but during the 1940s and 1950s its fastest streamliners covered the 152-mile Detroit-Grand Rapids segment in 2 hours and 40 minutes. A true Coast to Coast train terminating at Holland would add about 40 minutes to the schedule. But track, signaling and grade-crossing upgrades could cut those 1950s running times, making the Coast to Coast route extremely attractive for business, professional, family and leisure travel.

Who would use it—is the ridership there?

With its tracks, signals, stations and other critical infrastructure upgraded to handle modern passenger trains, the old Pere Marquette route would be ready to host multiple daily train frequencies tailored to the needs of business travelers, families, tourists and the large numbers of college students and faculty on the route.

A capital idea

The state capital, Lansing, roughly halfway between the two end points, is likely to generate large volumes of travel. States with their capitals located outside their largest cities—Illinois, Missouri, California, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and New York—are among the largest generators of rail-corridor ridership. On weekdays, metro-to-capital trains are busy with legislative staff, lobbyists, pressure groups, journalists and business people seeking state contracts. These riders shun driving because they expect to work en route.

And trains serving state capitals get lots of tourist business too, especially from school groups taking a field trip to observe government at work.

Forget Chicago—just focus on Michigan

But can a passenger rail service succeed without a giant metropolis at each end? Must all Michigan trains go to Chicago?

European experience suggests that giant-metro pairs are not essential for successful passenger rail corridors. Passenger trains can work just fine when there’s a big city at only one end.

Hey, Czech out these schedules!

Prague, capital of the Czech Republic, is famous for its history, architecture, and hilly, forested terrain speckled by stately public squares full of restaurants, wine bars and beer gardens. But it’s not a megalopolis. Prague’s population is a modest 1.3 million—way less than metropolitan Detroit.

And the second-largest city in the Czech Republic, Brno, the capital of Moravia, has only 380,000 people—fewer than metro Grand Rapids.

Prague and Brno are 180 miles apart and connected by 16 round trip trains per day.

Portugal’s capital and largest city, Lisbon, has only about 3 million people—less than the 4-million Detroit metro. Portugal’s second-largest city, Porto, 180 miles north, has 214,349 people—fewer than Grand Rapids.

Yet, according to the popular travel site “The Man in Seat 61,” Lisbon and Porto are connected by 14 morning rail round trips, 12 afternoon trains, seven evening trains and two night departures. The trains are a little slow by contemporary European standards, taking about three hours to make the trip. But the Portuguese government just announced it’s going ahead with a high-speed rail line that will cut that time in half.

Or consider Ireland. Dublin, the capital, has about 1.35 million people. Cork, 165 miles away, has about 140,000. The two end points are connected by 14 daily round trips that cover the distance in 2 hours and 32 minutes.

Short regional routes work in the U.S. too

But you don’t have to go to Europe to find a successful passenger-train corridors. Just ride one of the five daily Downeaster trains connecting Boston with southern Maine. Although the 145-mile route connects Maine with Boston via New Hampshire, the Downeaster service is essentially a Maine project funded by the Maine legislature and managed by the Maine-based Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority. Its mission is to provide fast, frequent, convenient and safe mobility for Maine’s residents and visitors. Half of its 12 stops are in Maine, with three in Massachusetts and three in New Hampshire.

And do they ever ride!

Kicked off in 2001 with four daily frequencies between Boston and Portland, the Downeaster service has grown to five daily round trips, and the northern terminus has been extended 21 miles to Brunswick (with a stop in Freeport, where the big attraction, just a short walk from the station, is the L.L. Bean outlet mall). After a brief dip during the COVID pandemic, annual ridership came roaring back in 2023 to hit an all-time high of 516,723. Fifty-five percent of the ridership was to or from stations in Maine—no small matter in a small state that depends heavily on tourism.

Who rides? Maine residents who work in Boston or its suburbs and Maine students studying at one of Boston’s prestigious universities. Maine residents seeking treatment at Boston’s prestigious research hospitals. Maine business people traveling to conferences in Boston.

Boston-area business people traveling to conferences in Maine. Families visiting relatives all up and down the picturesque and historic coastline.

And in the summertime Bostonians seek relief from the heat by traveling to Old Orchard Beach, Me., where the railroad tracks literally form the western boundary of the city’s eponymous beach. Passengers wear their swimsuits under their street clothes and descend from the platform right onto the sand.

“They bring their folding chairs and umbrellas and beach toys right aboard the train and when we get to Old Orchard Beach they just stride off to the shore,” said NNEPRA’s veteran executive director, Patricia Quinn.

Maine basically runs it

Amtrak owns the three Downeaster trainsets and operates them over tracks in Massachusetts owned by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and north of the state line on the main line of CSX Corp. The consists are double-ended shuttle trains so they don’t have to be turned at either Brunswick or Boston. Each train has a capacity of 306 passengers. In between are four coaches and a fifth car with business-class 2+1 seating at one end and cafe-lounge at the other end.

The cafes are the only food-service cars in the Amtrak system not operated by Amtrak. NNEPRA, as the trains’ sponsor and financier, selected Boston-based DineNex, a major food-service contractor to corporate cafeterias, hospitals and nursing homes, to prepare and serve all on-board meals and beverages.

Is Downeaster the model for Coast to Coast?

Like the proposed Coast to Coast corridor, the Downeaster route connects a large metro area with a series of smaller outlying communities. While Boston proper has only 655,000 people, its total metro area is 4.9 million, generating a ridership potential very similar to that of metro Detroit, with its population of 4.2 million.

But there the resemblance ends. Unlike the Coast to Coast route, the Downeaster’s downline communities are comparatively small. The largest destination on the route, Portland, has a little over 68,000 people, way smaller than Lansing-East Lansing, with more than 350,000, and well below Grand Rapids, with its metro population of a million. The current terminus of the Downeaster route, Brunswick, has only about 20,000 people, fewer than the proposed terminus of the Coast to Coast route, Holland, which has just over 33,000.

Those numbers alone suggest a Coast to Coast corridor in Michigan would attract substantially more ridership than the Downeaster. But when you sum the number of stops and the sizes of their respective populations the Coast to Coast’s potential ridership simply skyrockets by comparison.

Outside their home terminal at Boston the Downeaster trains make eleven stops that have a total population of 313,024.

But a Coast to Coast train leaving Detroit would stop at only four cities with a total population of nearly 2 million. Grand Rapids has more than 200,000 people and with its suburbs reaches nearly a million.

And while the Downeaster route serves very few college students outside of college-heavy Boston—Bowdoin College at Brunswick has an enrollment of only 1,200 and the University of New Hampshire at Durham has about 15,000—a Coast to Coast rail service across Southern Michigan would serve the largest state university in the Midwest—Michigan State at East Lansing, with an enrollment of 53,000+, along with a series of smaller colleges in Grand Rapids and Holland.

Bend the route and bump up the ridership three ways!

In 2013 Transportation Economics & Management Systems of Frederick, Md., completed a study of the Coast to Coast corridor to ascertain its potential ridership and estimate the cost of transforming it from a freight-only railroad to a modern passenger/freight main line. The TEMS engineers predicted the corridor would attract large volumes of passengers, but it concluded its appeal would be enhanced dramatically if its route were to be altered slightly.

Instead of following the original Pere Marquette alignment the full distance between Holland and Detroit, TEMS wrote, the trains should follow that line only as far east as Howell, 54 miles northwest of Detroit in Washtenaw County. At Howell the trains would turn south onto the single-track main line of the former Ann Arbor Railroad and follow that line into Ann Arbor, where they would switch onto the 110-mph Chicago-Detroit Wolverine main line and follow it for the next 38 miles into Detroit.

TEMS estimated the total cost of upgrading the line—including new trackage, signals and a bridge over the Huron River to switch the trains from the Ann Arbor alignment to the Wolverine main line at Ann Arbor—at $436 million. But that’s a 2016 figure made obsolete by inflation. The total today would be closer to $1 billion.

But it’s money well spent. The Ann Arbor diversion would add a small amount of mileage to the route but would dramatically improve its passenger catchment area by adding a second Big 10 college town—Ann Arbor—with its population of 123,000 and its University of Michigan enrollment of 51,225 to the 50,334 MSU enrollment at East Lansing just an hour west.

The Ann Arbor stop also opens up West Michigan to the giant University of Michigan’s medical school and hospital complex with more than 3,000 hospital beds, an academic staff of 3,700 and an administrative staff of 17,500.

And according to TEMS, the diversion into Ann Arbor would cost the Coast to Coast trains no additional time, because the state-owned Wolverine trackage already has been upgraded for 110-mph speeds over the 28 miles between Ann Arbor and Dearborn. Any time lost diverting to Ann Arbor would be made up on the fast track between Ann Arbor and Dearborn, the latter capable of generating its own substantial ridership. The new Amtrak station at Dearborn—pop. 104,000—not only attracts large numbers of passengers from the Detroit suburbs but sits just across the tracks from one of Michigan’s largest tourist attractions, Greenfield Village and the Henry Ford Museum.

That little diversion from Howell to Ann Arbor doesn’t just enhance the Coast to Coast’s ridership potential. It also solves two other problems Michigan’s transportation planners have been struggling with for two decades: how to provide an effective commuter service from exurban Howell to the big employment centers in suburban Ann Arbor, and how to fund commuter trains between Dearborn and Detroit. By including the Howell-Ann Arbor diversion the Coast to Coast line becomes a trans-Michigan intercity corridor with two short-distance commuter-rail corridors embedded in it—the kind of high-output “three-fer” deal that makes economists drool.

Do it now

“Our lessons learned are that nothing happens by accident,” said Patricia Quinn. “We work it every day to make sure we’re serving the right people and the right places with the right services.”

If Maine can do it, Michigan certainly can. The Downeaster may have more “right places,” but the Coast to Coast route has five times as many people. Coast to Coast trains can give them a whole new measure of mobility.

And a whole new measure of safety. The Michigan State Police are reporting that the 2022 accident rate for I-96 between Grand Rapids and Detroit included 734 crashes with injuries and 18 fatalities.

Isn’t it about time for some trains?

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!