Engineering Firm Chosen to Design Critical High-Speed Rail Segment in California HDR has been awarded a five-year contract to deliver engineering and design services for a 54-mile segment between Palmdale and Victorville. This is a critical connection between...

Guest post By F.K. Plous

The case for 10 trains a day to Champaign

A drama currently under way on the freight side of the industry could have major implications for passenger-train development along a key corridor in the Middle West. Even if you have no interest in freight railroading, stay with me here. Your understanding could lead to a passenger-rail breakthrough.

Why a big freight-rail merger opens the way to more passenger trains

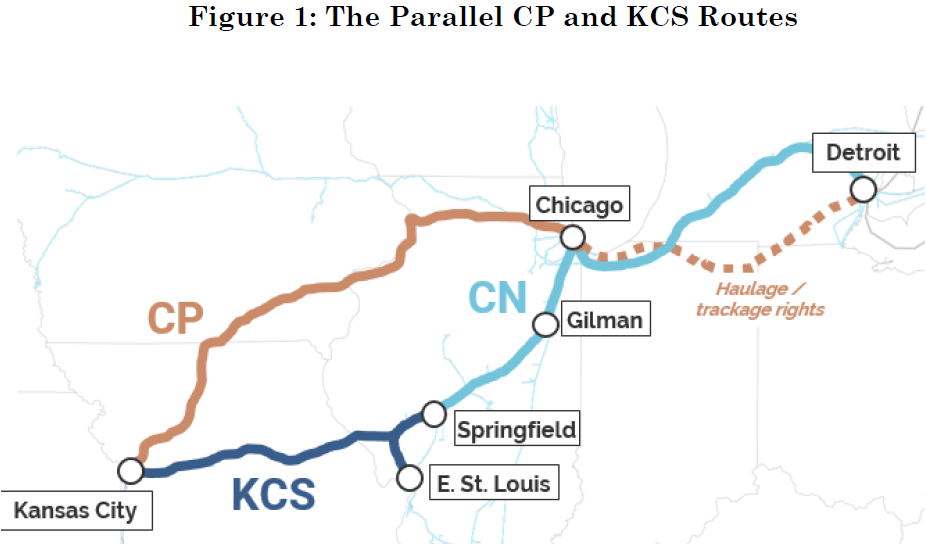

As many rail advocates know, the Canadian Pacific Railway has filed notice of its intent to merge with the Kansas City Southern Railway. If the U.S. Surface Transportation Board (STB) approves, the merger would create the longest single railroad in North America, including a coast-to-coast line across Canada, a branching main spearing southeast across North Dakota to the Twin Cities and Chicago and a central spine running from the Midwest through Texas and all the way to Mexico City.

The STB usually approves railroad mergers if they lead to greater competition. Shippers and their customers benefit when a merged rail system offers a greater choice of carriers, routes and rates. CP+KCS does exactly that by breaking the BNSF and Union Pacific duopoly over single-carrier hauls between the Upper Midwest and Texas. Once the merger is approved there’s a new kid on the block.

CN says, “Wait a minute”

There’s just one glitch standing in the way of STB approval: CP’s giant rival, the Canadian National Railway, claims one feature of the proposed merger will leave shippers with fewer choices in a prime shipping lane—Chicago-Kansas City.

Historically, rail shippers seeking service between Chicago and Kansas City have chosen the BNSF Railway’s former Santa Fe Railway route. At 437 miles of double track it’s the shortest and fastest way to go.

But Canadian Pacific has its own route from Chicago to Kansas City, the former Milwaukee Road’s main line running due west from Chicago to Savanna, Ill., then across the Mississippi and southwest across Missouri to Kansas City. The CP route is 67 miles longer than the BNSF’s, and it’s all single track, so it’s slower than the BNSF.

But with its direct new connection to the Kansas City Southern at Kansas City, CP’s former Milwaukee Road route suddenly becomes more valuable by offering shippers a faster, single-carrier way to get their freight to Mexico (and to many Oklahoma, Texas and Gulf Coast points not served by BNSF or UP).

There’s just one downside to this brisk new level of inter-railroad competition. KCS owns a third piece of railroad accessing Kansas City from the east–a 290-mile single-track line connecting Kansas City with Springfield, Ill. Neither KCS nor CP has track east of Springfield, so the little branch is something of an orphan lacking the potential to capture much traffic headed for Kansas City, Texas or Mexico. CP and KCS management agree that once the merger goes through and CP’s old Milwaukee Road route start feeding KCS at Kansas City the new company will reduce maintenance on the Springfield line and use it only for local access, not through freight.

Canadian National Counters

But CP’s rival Canadian National Railways does have track serving Springfield, a 112-mile line that runs northeast and connects with the company’s Chicago-New Orleans main line at Gilman, 109 miles south of Chicago. CN wants to buy the Springfield Line from KCS, join it to its existing track from Springfield up to Gilman, invest $250 million fixing the route up for 40 mph freight service and make Chicago-Kansas City into a genuinely competitive 3-railroad market offering shippers a robust choice of rates and routings capable of taking thousands of truck movements off the highway. CN says if it can join the KC-Springfield line into its own system it could offer the market not only a third link between Chicago and Kansas City but also a direct service over its own track east of Chicago to Detroit and the major traffic-generating areas in Ontario and Quebec.

The STB, which favors vigorous inter-railroad competition, is likely to grant CN’s petition. And if CN proceeds with its effort to win new traffic to the rebuilt Kansas City-Springfield-Gilman route, those rails will start reverberating with the sounds of big diesels hauling long trains of freight cars.

But what’s good news for the underutilized Kansas City-Gilman trackage could become bad news once the new freight trains reach Gilman and join CN’s Chicago-New Orleans “Main Line of Mid-America” for the final 110-mile leg into Chicago. That line’s already congested with freight traffic, and new traffic flowing to a rehabbed Springfield Line will only make the congestion worse.

Time to go back to the future?

When Canadian National bought the Illinois Central Railroad in 1989, virtually the entire Main Line of Mid-America was double-tracked, and the busy 39 miles between Peotone and Chicago actually had four tracks—two for freight and two for passenger trains. To save on track maintenance and enhance productivity, CN cut the two tracks south of Peotone down to one and installed Centralized Traffic Control with long sidings so that trains could pass each other.

The strategy worked. The Main Line of Mid-America became a highly productive, money-making part of CN.

Since 1989, however, freight-traffic growth has overwhelmed the single-track configuration, often delaying Amtrak’s City of New Orleans and its two daily state-sponsored Chicago-Carbondale round trips. If a new surge of Chicago-Kansas City freight traffic were to start using the line between Chicago and Gilman, the on-time performance of passenger trains would deteriorate further, stifling an exciting potential growth in ridership.

Time to put the double track back?

But with a little help from the state and federal governments, CN’s looming traffic crunch between Chicago and Gilman could be turned into a win-win-win for CN’s freight customers, Amtrak passengers—and thousands of new riders Amtrak would attract once the trains started running on time AND once the number of frequencies was increased.

The key is to restore the missing second track—and not only on the Peotone-Gilman segment but over the remaining 47 miles between Gilman and Champaign. If the entire 129 miles between Chicago and Champaign were restored to double track the route would be able to handle growth in both passenger and freight traffic–much as the Canadian Pacific’s 85-mile double-track line between Chicago and Milwaukee handles seven daily Hiawatha round trips plus the Empire Builder plus over a dozen daily CP freight trains.

Restoration of the missing second track not only will allow CN’s trains to run on time but Amtrak’s as well.

Most important, a second track will allow the Illinois Department of Transportation to support the additional Amtrak frequencies needed to turn the Chicago-Champaign segment into a true high-frequency, high-convenience rail-passenger corridor operation offering so much utility, convenience and safety that large numbers of travelers between Chicago and Champaign-Urbana will simply switch from car to train. A second track would permit the Amtrak service on the 129-mile Chicago-Champaign segment to swell from the current two daily round trips to as many as a dozen.

Simplicity itself

Technologically the task is no challenge. Short, double-ended trains could shuttle back and forth between Chicago Union Station and Champaign—with stops at Homewood, Kankakee, Gilman and Rantoul—in about two hours regardless of weather.

A “memory schedule”–say, departures from each end at 15 minutes after the hour—would make train times easy to remember and would reinforce the corridor’s existing advantages. “Last-mile” problems are minimal: The 20-year-old Champaign Transportation Center is a virtual showcase of modern public transit: every incoming train is met by scheduled buses reaching deep into the University of Illinois campus and most of the neighborhoods in Champaign and Urbana. And Amtrak’s Chicago Union Station offers easy transfers to most of Metra’s commuter-rail network.

But where will all those passengers come from? They’re already there.

But is there enough potential ridership actually support 10 daily round trips? Are there really that many people in Champaign-Urbana who want to travel to Chicago (and Chicagoans who want to travel to Champaign-Urbana)?

To get an idea of the potential market, let’s look at an adjacent corridor that’s almost as long as the Chicago-Champaign segment of the Illini/Saluki service. It’s the northern end of the 285-mile Chicago-St. Louis Lincoln Service Corridor. The Lincoln Service is the busiest of the three state-supported corridors in Illinois, carrying some 513,000 passengers in pre-COVID 2019.

But the busiest single segment of the Lincoln Service Corridor is the northern 124 miles between Chicago and Bloomington-Normal. In 2019 the number of Amtrak passengers handled at Bloomington-Normal was 229, 894—the single busiest station on the whole corridor. Springfield was way behind with 161,319 passengers.

College towns are key to buildup

There’s no mystery why Bloomington-Normal is the busiest stop on the Lincoln Service line. Normal is a college town, home of Illinois State University. ISU has a huge enrollment of students from the Chicago area, the new station is a short walk from the campus, and the train is the fastest, safest, most comfortable way to get to Chicago. ISU staff and faculty also visit Chicago a lot, and they use the train too. So do substantial numbers of Bloomington and Normal residents with no connection to the university. The train service is good, so they ride the train.

Now let’s move a few miles east to the Illini/Saluki Corridor. The twin college towns of Champaign and Urbana are almost the same distance from Chicago as Bloomington-Normal, 129 miles versus 124 miles. But the demographics at Champaign-Urbana are very different. While Bloomington-Normal has a population of 128,410 non-student residents and 21,000 ISU students, all the numbers at Champaign-Urbana are almost twice as large. The University of Illinois has an enrollment of 44,087 and the combined population of Champaign and Urbana is 226,323.

And since the rail corridors linking both college communities to Chicago are about the same length and the travel time in both corridors is about two hours, train ridership between Champaign and Chicago should be about twice what it is between Bloomington-Normal and Chicago, right? Wrong.

What’s the problem with Champaign-Urbana?

Where the Bloomington-Normal station handled 229,894 Amtrak passengers in 2019, the Champaign Transportation Center handled only 180,427.

Why? Based on the differences between the two populations Champaign should have been generating almost twice as many Amtrak tickets as Bloomington-Normal: the population is twice as big and the rail distance and travel time to Chicago are the same, so–what’s wrong? Why isn’t Champaign generating twice as many Amtrak ticket sales as Bloomington-Normal?

There can be only one explanation: frequency. Bloomington-Normal is served by five daily round trips while Champaign offers only three. Train travel between Chicago and Champaign-Urbana just isn’t as convenient as it is between Chicago and Bloomington-Normal because people in Bloomington-Normal have a wider choice of travel times. If they’re headed up to Chicago they can leave at 7:31 a.m., 10:14 a.m., 11:39 a.m., 5:56 p.m. and 8:36 p.m. If they’re returning from Chicago they can leave at 7 a.m., 9:25 a.m., 1:45 p.m., 5:15 p.m. and 7 p.m. Because all trains continue on to St. Louis, service to Downstate stops such as Lincoln, Springfield, Carlinville and Alton is just as convenient.

Compare that to the huge gaps in the schedules between Chicago and Champaign. The first train out of Chicago leaves at 8:15 a.m., and then there’s a nearly 8-hour gap until the next train at 4:05 p.m. The only other departure is at 8:05 p.m. Northbound the choices are just as sparse, with departures from Champaign at 6:10 a.m., 10:14 a.m. and 6:59 p.m. (Note that nearly 9-hour gap!)

Based on the relative populations of these two big college communities and their almost identical distance from Chicago, the Champaign-Chicago segment of the Illini/Saluki Corridor should be generating not 180,427 passengers per year but something closer to 350,000, and the number of daily frequencies should be at least six with specific plans to grow the number to ten—a shuttle operation, in other words.

Let’s you and me and IDOT raise some money

But you can’t run that level of service on a single track jammed with freight trains. The Illinois Department of Transportation needs to seize the opportunity arising from Canadian National’s need for Kansas City Southern’s Springfield Line and negotiate with CN for a public-private funding agreement to reinstall that second main track all the way from Peotone to Champaign so the state can fund a Chicago-Champaign Amtrak shuttle operation capable of attracting half a million passengers per year.

The numbers tell us those riders are there already. All they need is some some trains.

And all the trains need is some track.

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!