Amtrak is boasting about the early success of its Mardi Gras service – two round trips a day between Mobile, AL and New Orleans, with for intermediate stops in Mississippi: Pascagoula, Biloxi, Gulfport and Bay St. Louis. The service started rolling in August. In its...

When the Illinois General Assembly passed its $1.5 billion transit package, it did something more profound than stabilize budgets or prevent service cuts. It fundamentally reconceived the role of passenger rail and public transportation in the state’s economic and social fabric—and wrote that vision directly into law.

The legislation introduces the term “regional rail” into Illinois statute not once but twice and mandates a working pilot program within 14 months. It makes intercity passenger rail eligible for hundreds of millions in state transit capital funds for the first time in history. And it creates institutional machinery—committees, oversight officers, coordination mandates—designed to knit together trains, buses, sidewalks, and trails into a genuinely integrated transportation network.

This isn’t a maintenance bill. It’s a systems-building bill. And it positions Illinois to do something few American states have attempted: build a modern, frequent, interconnected railway network that treats mobility as essential infrastructure rather than a social service.

Get Involved

Tell Congress: It’s time to reconnect the country with high-speed and regional rail!

Intercity Rail Gets Transit Capital Funding for the First Time

For decades, American transportation policy has maintained an artificial distinction: “transit” meant local buses and commuter rail, funded through transit agencies and programs. “Intercity rail” meant Amtrak, funded through federal appropriations and treated as an entirely separate system. The two lived in different budget categories, answered to different priorities, and rarely coordinated.

Illinois just blurred that line.

The legislation makes intercity passenger rail eligible for funding from both the Downstate Transit Improvement Fund and the Downstate Mass Transportation Capital Improvement Fund. That’s a conceptual breakthrough. Illinois now treats intercity rail as part of its public transportation system, not as a separate program.

What can this money buy?

-

Station construction and improvements: upgraded platforms, accessible facilities, passenger amenities

-

Grade separations: eliminating at-grade crossings that slow trains and create safety hazards

-

Track and signal infrastructure: allowing higher speeds, improved reliability, and capacity for additional trains

-

Planning and engineering studies: laying groundwork for route extensions to new destinations

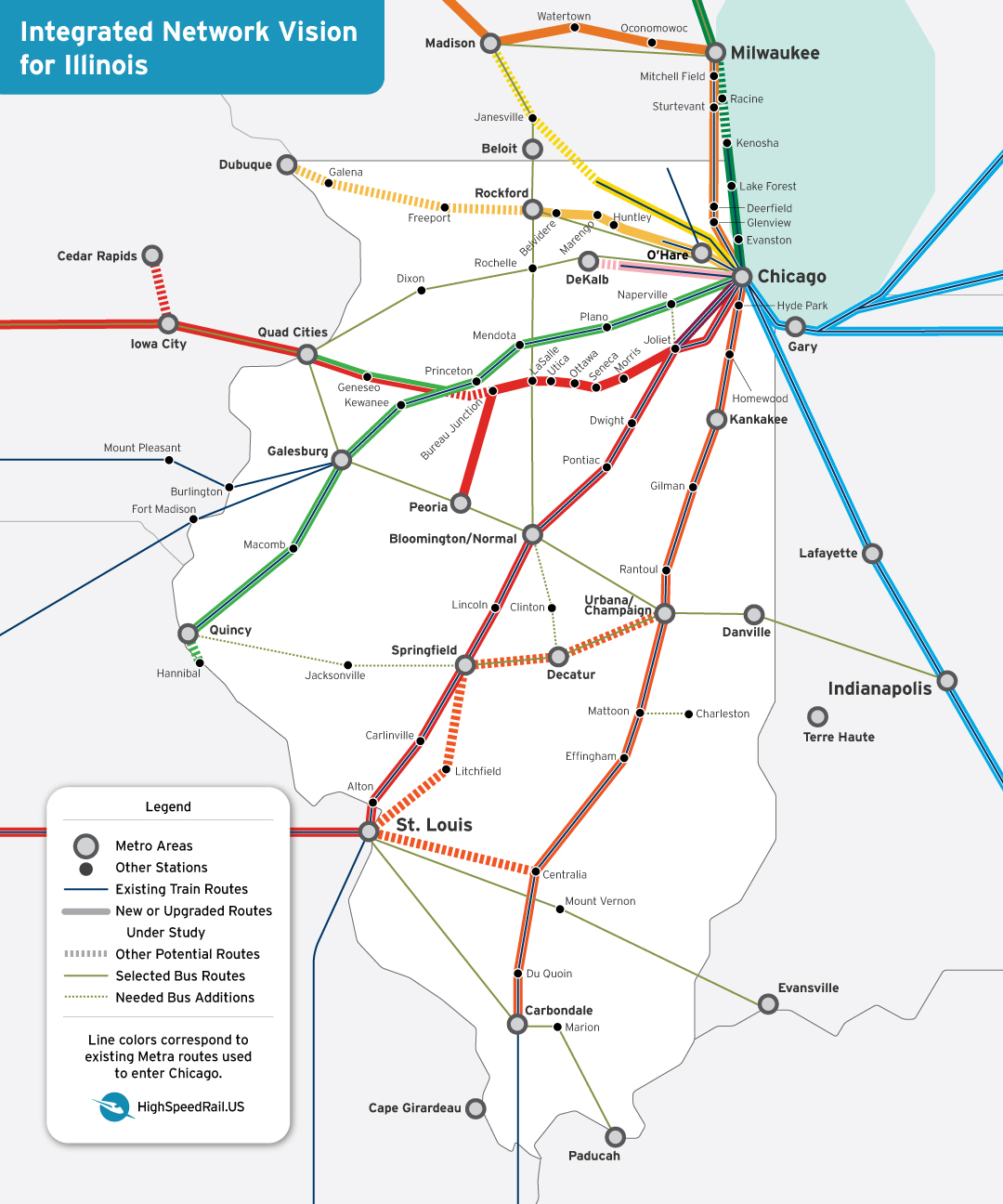

There are statutory caps on total intercity rail spending, but the principle is now established: a train from Chicago to Quincy or Carbondale is part of Illinois’ transit network—just like a bus route in Peoria or a commuter train to Naperville. They’re all public transportation. They all serve mobility needs. They all deserve state investment.

The legislation specifically calls out two planning studies that point to the state’s ambitions:

Joliet Hub Study: The Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) must conduct a planning study on improvements needed at the Joliet train station to enable potential extensions of passenger rail service to Peoria and other locations outside the six-county Chicago metropolitan region. This positions Joliet as an intermodal gateway—a place where Chicago-area commuter trains, intercity trains to downstate destinations, and eventually bus connections can converge.

Kankakee Extension Study: Metra must study extending the Metra Electric Line from its current terminus at University Park south to Kankakee, a city of 26,000 located 56 miles from downtown Chicago. The study matters not just for Kankakee but for what it could enable beyond: with two new tracks and overhead electric power, this corridor could extend to Champaign, effectively replacing that segment of the Saluki with hourly (or better) service and trips under two hours. That’s achievable with the right infrastructure—and it would transform access to jobs, education, and economic opportunity for every community along the route. The study’s scope and assumptions will determine whether Illinois thinks incrementally or builds the foundation for a true intercity rail corridor.

The Regional Rail Breakthrough

A striking innovation in the Act is the explicit embrace of “regional rail”—a term that signals a complete departure from the commuter rail model that has defined suburban train service for over a century.

Traditional commuter trains run in one direction during morning rush hour (toward downtown) and the opposite direction during evening rush hour (away from downtown). Midday service is sparse. Weekend service is limited. The model assumes a 9-to-5 office workforce commuting to a central business district—a reality that describes an ever-shrinking share of actual travel patterns.

Regional rail, by contrast, runs frequently throughout the day in both directions. It serves reverse commuters, midday travelers, weekend visitors, and anyone whose schedule doesn’t align with traditional peak hours. It functions like an urban metro system extended to suburban and exurban territory—turn up and ride, rather than plan around a timetable.

The legislation doesn’t just endorse this concept abstractly. It requires action. By January 1, 2027, Metra must implement a regional rail scheduling pilot program on the Rock Island Line, specifically to improve transit access for residents of Will County and southern Cook County. This line serves South Side neighborhoods like Beverly and Morgan Park, extends through Blue Island and Tinley Park, and terminates in Joliet—a mix of urban, suburban, and edge-city contexts ideal for testing all-day, bidirectional service.

But the mandate goes further. The new Northern Illinois Transit Authority (NITA) – which replaces the RTA – must adopt service standards by December 31, 2027, and those standards must explicitly address “the transition of commuter rail in the metropolitan region to a regional rail service pattern or the retention of commuter rail with additional regional rail service.” The law directs NITA to look at global best practices from metropolitan areas with comparable populations and economies, develop transit propensity metrics, and create line-level performance indicators that get published monthly.

This is not aspirational language. It’s prescriptive. Illinois has legislated a transformation in how suburban rail service operates.

Other Key Priorities

Opening the South Shore Line to the Loop and South Side – Riders waiting at Metra Electric stations like 57th Street or Van Buren will no longer have to deal with the absurdity of not having the option of taking a South Shore train – that stops at their station – to their destination. The legislation prohibits Metra from entering into any agreement that blocks the Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District (which operates the South Shore Line) from picking up passengers at Metra-operated stations.

Bus Rapid Transit and Priority Operations – The Act requires IDOT, the Tollway, and local governments to work with NITA and transit operators to enable bus rapid transit and bus-priority on expressways and major roadways. It calls for coordinated evaluation of operational strategies and technologies—such as bus-on-shoulder running, queue jumps, signal priority, and dedicated lanes—to improve speed and reliability. The aim is straightforward: buses carry far more people per lane than cars, and the network should be designed to reflect that efficiency.

Making Transit Accessible – The legislation makes access part of the transit system itself. When roads are rebuilt, sidewalk links to stops, boarding pads, and shelters can be included as standard elements, with NITA support—folding first-/last-mile needs into normal street work instead of treating them as extras. A new Transit to Trails Grant Program helps connect transit riders to parks and outdoor areas, prioritizing communities that historically lack access to nature. And by allowing transit agencies to partner on residential and commercial development within a quarter-mile of public trails, the law encourages walkable neighborhoods that support ridership while generating value for the system—still under local land-use oversight.

Institutional Changes: Committees and Coordination Mandates

Good policy intentions often fail because no one is specifically tasked with implementation. This legislation creates clear accountability structures.

Transit Integration Policy Development Committee – Housed within IDOT, this committee is designed to embed transit considerations directly into the state’s roadway planning and project delivery. It brings together IDOT leadership, modal and highway staff, regional planners, and local transportation partners to coordinate early input on projects, identify and strengthen transit corridors, and develop roadway and design standards that support buses and intercity service. In essence, it shifts IDOT from a primarily highway-oriented agency to one that plans roads and transit together as a unified network.

One-Network, One-Timetable, One-Ticket Mandate – NITA is directed to oversee the metropolitan region’s public transportation system so it operates as an integrated network for riders. Service boards retain responsibility for fares, standards, and schedules, but the coordination requirement is explicit. The goal is seamless transfers, coordinated timing, and unified fare media—the hallmarks of mature transit systems worldwide.

Riders Advisory Council – NITA must appoint a 5–15 member Riders Advisory Council to advise on policies, service, budgets, fares, and service standards. The Council must receive staff support and time to review plans before Board action, and its membership must reflect the region’s demographic and modal diversity.

Transit as a Climate Strategy

The legislation explicitly connects transit expansion to greenhouse gas reduction. NITA is directed to work cooperatively with IDOT, the Tollway Authority, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, and other governmental units “to assist them in using investments in public transportation facilities and operations as a tool to help them meet their greenhouse gas emission reduction goals.”

The statute notes that the transportation sector accounts for approximately one-third of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions and that public transportation moves people with fewer emissions than other motorized modes. It establishes transit expansion as a core climate mitigation strategy and positions NITA to access climate funding streams that might not otherwise be available to transportation agencies.

The Bottom Line

Illinois has done something rare in American transportation policy: it has legislated a vision.

Most states approach transit as a problem to be managed—a service for people without cars, a budget line to be minimized, an operation to be kept from collapsing. Illinois is treating transit, intercity rail, and active transportation as assets to be expanded, improved, and integrated into a coherent network.

The Rock Island regional rail pilot will test whether frequent, all-day service can reshape travel patterns. The new intercity rail capital funding will determine whether downstate cities can be connected into a coherent network. The Transit Integration Policy Development Committee will show whether a historically highway-oriented agency can plan roads and transit together. And the one-network mandate will test whether multiple operators can deliver a unified rider experience.

Not every provision will work perfectly from the start—some will need refinement, funding, and institutional adaptation—but the direction is clear. Illinois is no longer trying to maintain a mid-20th-century system; it is building a 21st-century mobility network grounded in economic geography, diverse work patterns, climate responsibility, and real transportation choice.

The opportunity now rests in execution—and the country should pay attention. Illinois just became the most important state to watch.

A statewide regional rail network would make it practical to travel the state without a car.

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!