Help Expedite the Long-Distance Fleet Order Despite Congress appropriating substantial funding to replace Amtrak’s aging long-distance fleet, no order has yet been placed. This delay, paired with worsening equipment shortages and the retirement of damaged or outdated...

Guest Post By John Rodgers

Excellent passenger-rail service is about much more than where the trains go and how quickly they get there. The success of a rail service often hinges on frequency. When service is frequent enough to be convenient and useful for customers all through the day, the value of passenger rail multiplies—and a virtuous cycle develops. As ridership grows, it becomes politically feasible to fund further improvements, which then motivates states and the federal government to keep building out the network. High-frequency trains are thus the foundation for building the nationwide rail system that our country deserves.

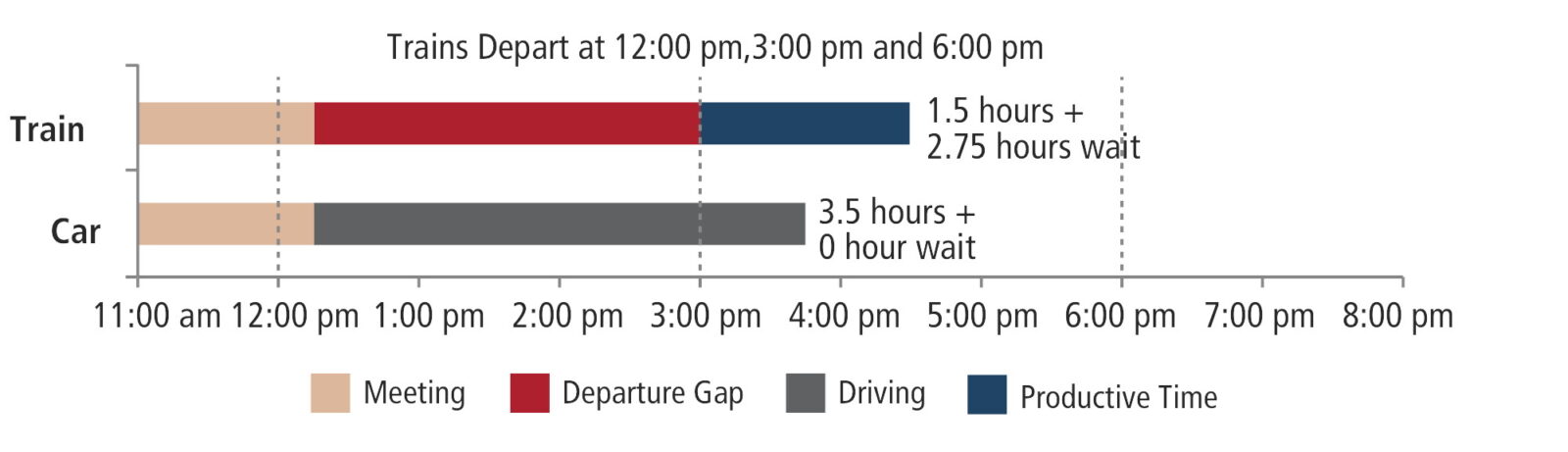

The best way to look at frequency in the context of a rail corridor is by looking at its ability to make rail travel competitive with automobiles. Potential riders need to see a clear benefit of riding the train over driving—taking into account overall travel time, cost, and potential productivity. The benefits of taking the train are diluted if frequency is not set at the appropriate level for the unique characteristics of a corridor.

For example, in a short corridor with bad rush-hour traffic, or a long corridor with a high-speed train, irregular frequencies will hinder the train’s effectiveness—but they can still be overcome because trains inherently perform much better than cars in these settings. But outside of rush hour—or on longer, slower speed corridors—frequency matters much more, as every minute spent waiting for the next train erodes the benefits of train travel. For these corridors, frequency can be the determining factor on whether the service succeeds.

While higher frequencies can save riders time, they also create greater flexibility for the wide variety of trips that people need to take. More trains mean more options for when to depart and return, more contingencies if plans change, and (in most cases) much greater ease of use. In countries with much more frequent passenger-rail service, most trains are partially or entirely unreserved, which opens the service up to an entire host of spontaneous travel needs. In many cases, this flexibility is just as important to riders as time saved.

What is frequency?

- Frequency is primarily conceived of as the number of trips operated over a certain route, or between a certain pair of stations. The scheduled time gap between trains—and how easy the schedule is to understand and memorize—are also key.

- Another important aspect of a service’s frequency is the service pattern. This refers to how many unique types of trips are operated in a corridor (e.g. regular, express, local) and the frequencies for each of those trips. A large variety of service types, or irregular frequencies for certain service types, makes the usefulness of a service harder to grasp for the average rider.

Why does frequency matter?

Since public forms of transportation, with a few exceptions, must run on a fixed schedule, users of public transit give up some control over their schedule—in exchange for a shorter travel time, or more productive free time (since they aren’t driving). Potential riders choose to drive because they can only reach their destination by transit when there is a scheduled service that can take them there, versus taking a trip on a whim if they have a car. This flexibility is one aspect of car travel that is not possible to replicate in a cost-effective way. Instead, transit infrastructure must be designed and operated to maximize its frequency and ease of use to close the flexibility gap as much as possible. If frequency is planned properly, most riders will choose the benefits of transit over the loss of flexibility from not driving.

There is also a two-fold efficiency argument for frequency:

- First, building and upgrading fixed infrastructure is expensive, and spending public funds on expensive projects that don’t facilitate the frequencies to make a service useful is a poor use of limited resources. It is important that funding for new infrastructure projects also be paired with funding to run enough trains to them useful. Underfunding frequency means a train service fails to utilize the hypothetical capacity created by infrastructure projects. In an intercity corridor, the goal should be to run close to 100% of new track capacity created by an infrastructure project. For example, funding a new bridge that allows for 10 trains per hour—but runs only four—is a huge, missed opportunity.

- Second, designing a service that runs infrequently, or only at peak hours, means that trainsets and crews spend more hours of the workday on downtime that could otherwise be used to provide additional service along a corridor. This downtime represents a portion of fixed and operational costs being spent for no benefit to the traveling public. While this downtime often can’t be eliminated entirely, proper planning can ensure that trainsets and crews spend most of the time during the workday running and providing service.

Low frequencies keep riders away

To cite a personal example, I have struggled to persuade friends to consider rail as an option on trips served by multiple trains per day out of Chicago. They believe the limited frequencies make rail a significantly worse travel option than driving:

- The Hiawatha corridor between Chicago and Milwaukee has the most trains on a route in the Midwest, yet it still falls short of usefulness for many potential riders, as the corridor should have at least hourly service all day. It currently has only seven round trips daily. This schedule means limited flexibility in terms of trip choice. You typically have to know what outbound and return train you will use before you decide to take the train to Milwaukee. Irregular and long gaps in service make turning up at the station and taking the next train infeasible. And a low overall number of round trips means that many trains sell out and require advance reservations, not to mention the risk of having to stand for the entirety of the trip. So, the flexibility of driving yourself wins out more than it should because of the lack of frequency.

- On the Wolverine Corridor between Chicago and Detroit, the low number of round trips means that there often isn’t a good after-work train to take when headed to Michigan. This mismatch makes a slightly slower car trip the only viable option. Hourly train service would greatly alleviate this problem, as a rider leaving work would have five trains to choose from between 2 p.m. and 6 p.m., instead of just two (at 2 p.m. or 6 p.m.).

- The lack of frequency also inhibits the ability of riders to connect to a service via other public transportation in an efficient way. Most Amtrak trips in Chicago have to start at Union Station, or rely on a car, as the low and irregular frequency of Amtrak trains—paired with the low and irregular frequency of Metra and suburban Pace service—means the odds of making a connection work outside of Union Station are prohibitively low. Most city dwellers will backtrack to Union Station instead of traveling in the same direction toward their destination on Metra and changing trains, as is common in other countries.

Frequency and infrastructure planning

We are left with the question of why rail projects in the US have fallen short—and what can be done about it. Too often in the US, rail projects plan frequencies inside-out by looking at the existing infrastructure and identifying the minimal possible service that can be added—then identifying what investments and steps are needed to get the minimal service running. Plans are made this way due to a lack of capital funding and political support for rail projects, which means that any sort of ambitious project for good service never gets past the feasibility phase, or never gets seriously studied at all. Planners who are fortunate enough to get a project to the implementation phase have had very few options and resources available to do more than the minimum possible service.

This inside-out approach to rail planning fails in two ways:

- First, it divorces the decision about frequency from the goals of the service, all but guaranteeing a disconnect between the two.

- Second, it leads to a worst of both worlds result, where large amounts of public funds get spent on rail infrastructure for limited rail service that is neither transformative nor useful for potential riders.

Worsening the funding problem is the fact that rail infrastructure ends up being extremely expensive in the US due to a number of factors that should be addressed alongside increased funding.

In order to deliver passenger-rail projects that succeed, frequency should be the primary consideration when making plans for rail infrastructure. If a public body decides that rail is the answer to a mobility need in a certain corridor or region, the step before implementation should be determining the appropriate frequency needed to provide service in the study area—and formulating a plan for what is needed to provide that frequency (e.g., extra tracks, flyovers, stations, stakeholder agreements, and funding).

The funding for passenger rail in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) is the first opportunity in a long time to begin focusing on frequency. But success in revolutionizing passenger rail planning hinges on three large developments:

- First, the funding stream specifically for passenger rail that was created in the IIJA must be renewed, at minimum. Ideally, it will be expanded significantly in the next surface transportation bill that follows the IIJA in 2026.

- Second, the projects receiving funding—and coming online by the end of the decade—must be better planned and more useful so that they can serve as shining examples to justify maintaining or expanding funding. Brightline West would be a perfect example, if it is built as currently planned. Voters and legislators should look at new IIJA projects and see something impressive that they also want for their home state, not a boondoggle or a non-factor.

- Third, planning needs to be institutionalized at the regional or federal level. Most corridors and contiguous networks would span multiple states, so regional or federal rail planning bodies must be created and empowered so that cross-border service plans and projects can be identified, agreed upon, and funded to ensure they are maximally useful. Planning processes should also be formalized further so these new federal or regional rail planning bodies make plans and decide on projects in the most transparent and least inconsistent way possible. If set up properly, these institutions should ensure that every project that moves forward in their jurisdiction fits into a larger plan to provide appropriate frequencies on its respective corridor.

If elected officials and planners take frequency into account on passenger-rail projects moving forward, the US will slowly begin catching up to the rail networks that our global peers possess. Then we can start reaping the numerous benefits that a well-developed rail system will create in terms of mobility, quality of life, and economic development.

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!