How High-Speed Rail Will Reduce Carbon Emissions Getting serious about climate change means getting serious about building great trains. Join Us The best way to cut carbon emissions while expanding our freedom to move Take a look at the numbers below from...

When you have an opportunity to expend the same or similar effort and money that would achieve the better of two outcomes, why not pursue the better outcome? That’s the decision Greater Cleveland has yet to make when looking at a transportation ingredient to two major waterfront development masterplans. One is the downtown lakefront development led by the Haslam Sports Group. The other is the Tower City Riverfront development led by Bedrock Real Estate. Both are supported by civic organizations and all levels of government.

The lakefront redevelopment could include a multimodal transportation center that unites the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s (GCRTA) underused light-rail Waterfront Line extension of the Blue/Green lines from Shaker Heights with Amtrak passenger rail services that serve Cleveland only at night. In the mid-2010s when I was the executive director of All Aboard Ohio, I urged the city and GCRTA to develop a lakefront multimodal hub. In today’s lakefront planning, the site of a transportation center hasn’t been identified but a 2016 study by the city and engineering giant WSP USA said the best place on the lakefront to put it was between the current site of the Amtrak station and East 9th Street. Provisions for expanding Amtrak service were not part of that site.

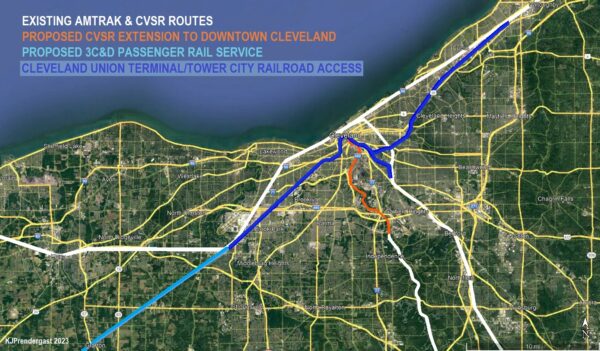

The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) in February requested federal funding for development plans to add 3C&D Amtrak service and expand services linking Cleveland, Toledo and Detroit. Meanwhile, the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA) is seeking planning funds for expanding existing services from Cleveland to Chicago and the East Coast. All are part of the Amtrak Connects US vision which could turn Cleveland into an Amtrak mini-hub with up to two dozen trains a day, boarding 500,000 to 1 million passengers per year — akin to putting a small-hub airport in the heart of Cleveland’s central business district.

To accommodate that many passenger trains would likely worsen rail freight congestion between downtown’s lakefront and Berea, dubbed the A Line, which saw nearly 50 daily Norfolk Southern freight trains 20 years ago and 70 trains per day now. Without major capital investment, rail shippers and travelers would face frequent delays. Adding tracks to this 12-mile stretch would be difficult owing to the many industries on one side of the mainline and GCRTA’s Red Line on the other. Another option would be to move rail freight traffic off the downtown lakefront to avail capacity for passenger trains. Both options may be considered if ODOT wins service planning money from the feds.

The existing Amtrak route is shorter, but hosts roughly 70 trains a day and is hindered by a draw bridge.

In 2003, I researched and wrote a peer-reviewed study for the Cleveland Waterfront Coalition and Green City Blue Lake about diverting half or all through rail freight traffic away from the downtown Cleveland lakefront. Such a diversion was projected to cost up to $150 million (or at least $250 million today) to triple-track Norfolk Southern’s B Line passing just south of downtown, much of which is the former route of passenger trains that served Cleveland Union Terminal (CUT) — today’s Tower City Center. Considering that price tag, another option should be considered, too — restoring intercity passenger rail service to Tower City Center.

The question is — if you have to expend so much effort to accommodate Amtrak Connects US vision on the lakefront, why not devote those energies toward putting the passenger trains back into Tower City Center? The lakefront might suffice if you’re convinced Cleveland will never see passenger rail expansion again. Even so, there’s significant value to be gained by uniting under one roof Greater Cleveland’s individually small and disconnected passenger rail services — Amtrak, GCRTA and Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR). In addition to GCRTA’s five-route rail transit system, you also get at Tower City its two (soon to be three) bus rapid transit lines and other GCRTA and intercounty bus services.

In addition to connectivity to more local and regional transit, Tower City is also better connected by foot to the central business district, including multiple hotels, office buildings, residential buildings, shopping, sporting events and entertainment venues including via climate-protected walkways. While the lakefront’s destinations are bound to increase with more development, so will Tower City’s.

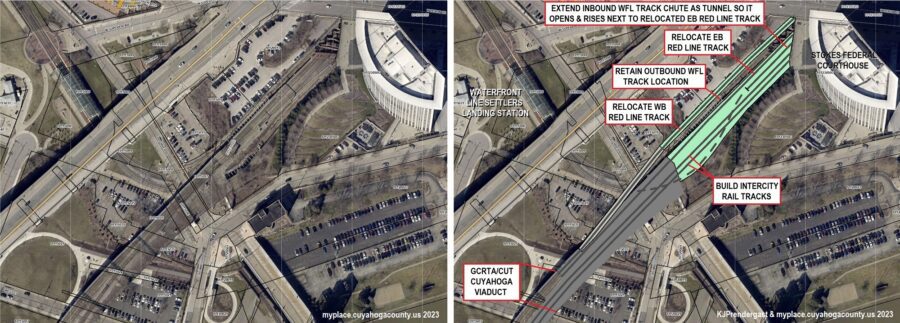

A federal court house stands where the tracks into Cleveland Union Terminal once ran, but there is a potential solution.

Perhaps you’ve heard restoring passenger rail to Tower City cannot be done because its south parking garage was inserted in 1990 where the railroad station was. Or that the west approach to the station and its former train storage yard were blocked by the 2002 construction of the Carl B. Stokes Federal Courthouse Tower. Recently, I suggested building a new right of way south of the courthouse tower to put a station between Huron Road and the riverfront for Amtrak and CVSR trains, and perhaps some future commuter rail service, with towers built above the tracks. But Bedrock understandably wants to move forward now on developing Tower City’s riverfront.

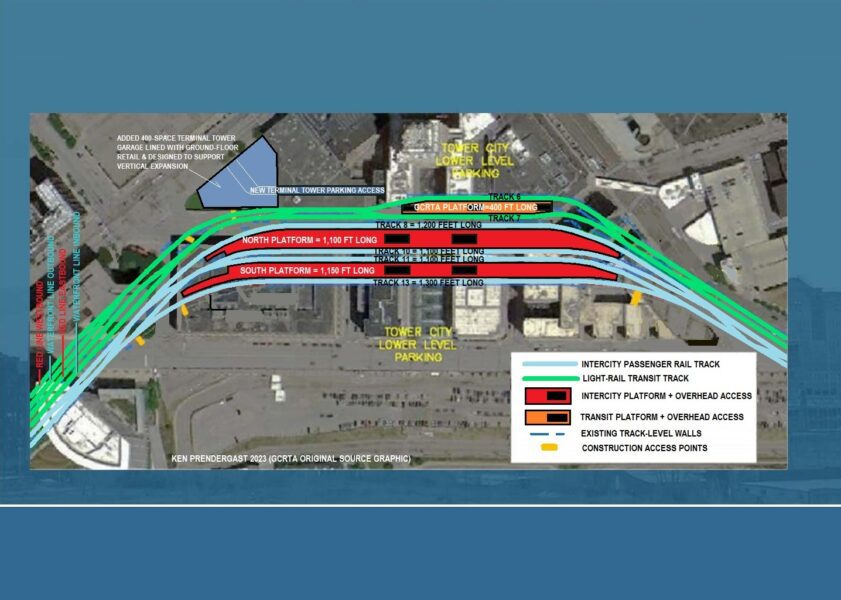

There’s another opportunity, however. Starting in 2026, GCRTA will be standardizing its rail system with new light-rail vehicles. It no longer needs such a large rail station at Tower City with one end for heavy-rail trains and the other for light-rail trains. GCRTA’s Shaker Rapid Transit station at Tower City has sat largely unused for 30 years, aside from offering a temporary station during the reconstruction of Tower City tracks in 2016 and 2020. With modifications, it could be GCRTA’s new Tower City station, opening up their current station for Amtrak and CVSR.

GCRTA’s station has tracks measuring up to 1,300 feet long — long enough accommodate Amtrak’s and CVSR’s longest trains. In fact, the southernmost track in GCRTA’s station was actually an intercity track prior the end of commuter railroad service to Youngstown in 1977 and the end of intercity rail service to CUT, last provided by Amtrak’s Lake Shore in late-1971.

The lakefront station’s primary advantages are that its expansion can be scaled up and track conditions allow Amtrak trains to achieve 79 mph quickly — but only when freight trains west through Berea and Lake Erie ships entering the Cuyahoga River don’t delay them. Amtrak now crosses the river on a lift bridge; CUT’s bridge is 100 feet high to clear all shipping. And the existing lakefront station’s capacity to handle more trains can be scaled up in increments — to a point. At some point of expansion, a big-city train station with multiple tracks and overhead access would be needed. Even then, there’s only enough room on the lakefront for two or three passenger-only station tracks. Tower City offers four track spaces with more if the south parking garage is trimmed back.

A Tower City station can be scaled up once GCRTA’s station is relocated and right-sized, its west approach tracks are shifted over by two track spaces and the curving, inbound Waterfront Line track tunnel is extended to open next to the inbound Red Line track. About 2,500 feet of the Red Line Greenway trail, which is set in a wide right of way, will need to be shifted over. At minimum, Amtrak can return to CUT if 7 miles of single track are restored, plus two tracks through the Tower City station, plus another 1-mile connecting track for CVSR. A two-track passenger-only mainline from Berea to the near-East Side and more station tracks can be added as passenger traffic expands.

On that initial infrastructure, rerouting four nightly Amtrak trains and extending to downtown CVSR’s six trains that run each day Wednesday-Sunday, will give a Tower City station a respectable start, providing 150,000 to 200,000 passenger boardings per year based on existing Amtrak use and 2003-projected CVSR ridership from a Cleveland extension.

Some of this data is old and needs updating. And many of the presumptions about being able to move GCRTA’s Tower City station into the old Shaker Rapid station and repurpose the existing GCRTA Tower City station for Amtrak and CVSR trains must be verified. But after running this idea by rail and transit planners, they say the idea has enough merit to warrant conducting engineering and feasibility studies of its potential. So, before any more changes are made to Tower City’s surroundings that might further complicate Cleveland’s ideal site for a train station, how about the city, county, GCRTA, NOACA and Bedrock put this inquiry on their to-do list?

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!