Marquee projects in big states attract most of the spotlight when it comes to trains. But when it announced the new Corridor ID program last year, the Federal Railroad Administration noted that “special emphasis will be paid to projects that benefit rural and underserved communities.”

That emphasis is important, because dozens of relatively low-profile projects will be critical to creating a truly national network of high-quality trains.

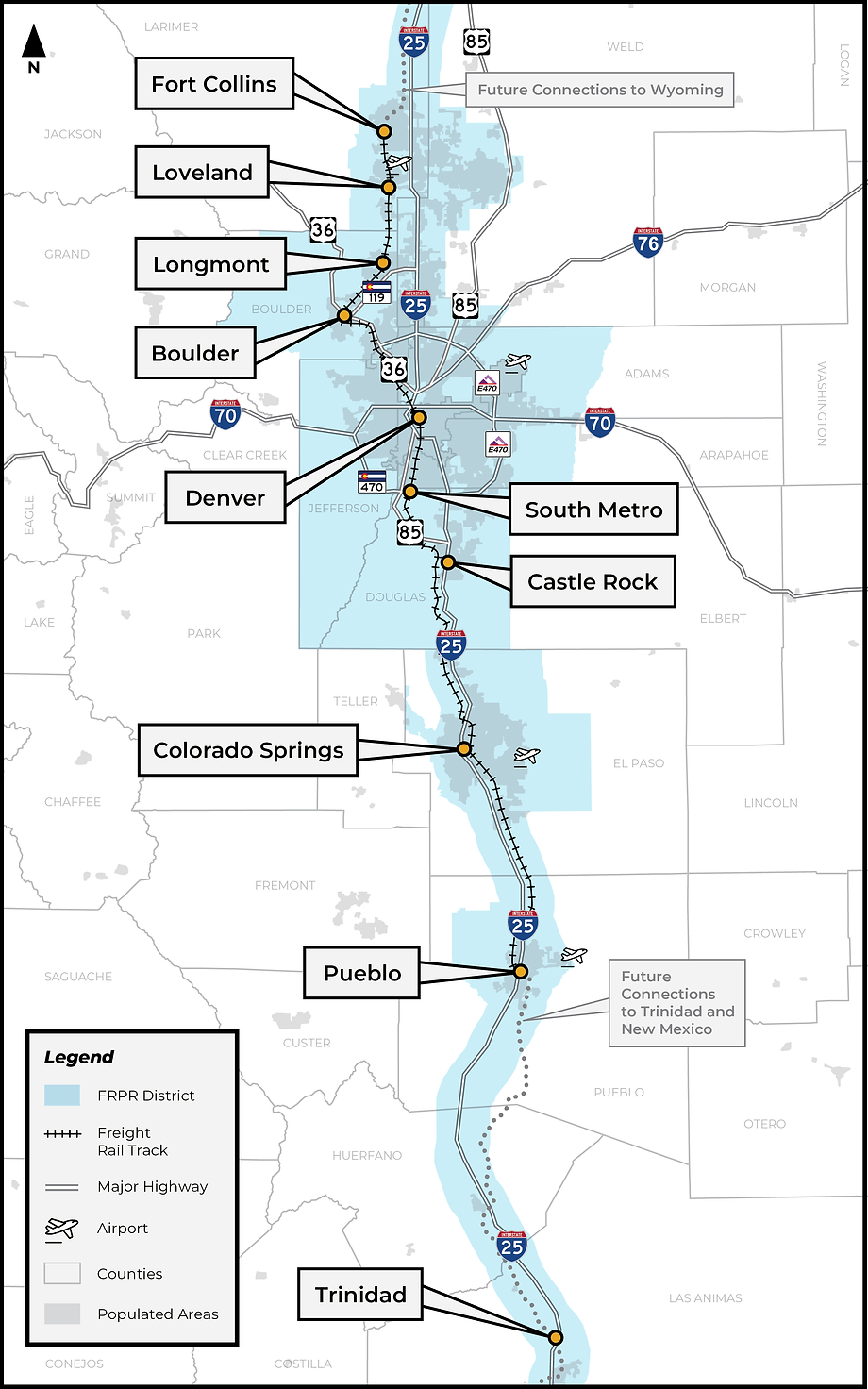

Consider one example: Colorado’s Front Range Passenger Rail (FRPR) corridor, which runs about 160 miles across 13 counties—from Fort Collins to Pueblo, with stops in Boulder, Denver, and Colorado Springs. (See previous HSRA coverage of the corridor here.)

Colorado lost most of its intercity passenger-rail service in the 1970s. Two long-distance Amtrak routes—the California Zephyr and Southwest Chief—now provide the state’s only passenger-rail service. Along with 68 other projects, FRPR was accepted into the Corridor ID program in early December.

Advocates, planners, and policymakers have worked for years to bring service to the corridor. In 2021, the state legislature created FRPR as a special taxing district and gave it the authority to ask residents to approve a new tax to fund train service.

That may happen via a ballot measure as soon as the 2024 election. But first, supporters are working to make sure the measure can win over a majority of voters. “We have to make sure we have a case to make to the public,” the chair of the Front Range district’s board of directors told Colorado Public Radio (CPR) recently.

Meanwhile, planning for the corridor is ongoing. Amtrak is a possible provider, though FRPR is weighing other options. The expected cost is between $2 billion and $6 billion, depending on the proposed route, speeds, frequencies, and other factors.

Three keys

The Front Range corridor underscores at least three important truths for rail advocates as we enter the Corridor ID era.

First, we have great opportunities to shape the planning process.

As we explain here, corridors must secure a 10 percent cost share to move from step 1 to step 2 in Corridor ID. Since the funding will usually come from a state legislature, policymakers have leverage in the details of project plans. Advocates, in turn, can play a big role in convincing policymakers to raise the bar.

So, as planning moves forward—and corridors nationwide design their own plans—our voices and demands matter. We need to push for more ambitious plans in the Front Range and elsewhere—i.e., faster speeds, higher frequencies, and state rail plans that make passenger-rail, transit, and bus systems work together as integrated units.

Second, the Corridor ID program is boosting the FRA’s presence and visibility in corridor planning—which could prove to be a boon, both for local projects and the development of a national network.

For example, the FRA’s administrator, Amit Bose, met with Colorado Gov. Jared Polis (D) in mid-December to discuss the Front Range Passenger Rail project. The meeting “was attended by a coalition of supportive legislators, local leaders, advocacy groups and representatives of other interests,” Colorado Public Radio reported.

Such meetings are are important because they generate media coverage; build relationships between local, state, and federal agencies; and give train advocates a great way to engage with local and state officials in person. Hopefully, we’ll see more of them—especially in many interior states where projects get less attention than high-profile, high-speed lines underway or being planned.

Third, having an influential, all-in champion for high-quality trains makes a huge difference.

As always, grassroots advocates have played a crucial role in building energy and momentum for FRPR. But it’s an immense benefit that Gov. Polis uses his megaphone to sell it to the public, tout its benefits, and keep it moving forward.

In September, for example, Polis took a test run of a prototype, hydrogen-powered train—with two train cars full of elected local and state officials on board—to build support for FRPR.

“This has been planned for decades, and it’s time to just get it done,” he told a reporter on the trip. “We’re going to do everything we can to make this available as soon as possible.” After the meeting with FRA head Bose last week, Polis emphasized that trains were key to addressing Colorado’s affordable-housing and carbon-emissions challenges. “The fact is that Coloradans are ready for Front Range Rail,” he said. “I would argue that we were ready five or 10 years ago, but we’re certainly ready now.”

In his own comments after the meeting, Bose said that “what’s happening in Colorado is just such a good model.”

Determined advocates. Engaged state and local officials. A governor with a passion for passenger rail. All of them pulling together to bring high-quality trains to a region that’s been neglected for more than half a century.

That’s a good model indeed. Let’s take it nationwide.

Take Action

Ask your Governor to think big and plan for success with the state’s new corridors.