The railroad Brightline today broke ground in Nevada on its new Brightline West project. Brightline will use trains traveling up to 200 miles per hour to cut the travel time between Las Vegas and Los Angeles in half. The company already operates successful trains...

Chicago and the Midwest can’t afford to lose the region’s intercity bus hub. The mayor and governor must act now.

Chicago is at risk of losing its intercity bus station. Greyhound’s terminal in downtown Chicago is up for sale. Without quick action by the City and/or State, it will be torn down and replaced with a high-rise. It is urgent for Mayor Johnson and Gov. Pritzker to work together to buy this critical transportation asset and help it grow its traffic.

If the connection between a bus station and high-speed rail isn’t obvious, here’s why train advocates should care about the fate of Greyhound’s Chicago terminal.

If the connection between a bus station and high-speed rail isn’t obvious, here’s why train advocates should care about the fate of Greyhound’s Chicago terminal.

Ultimately, we seek to use better travel options as a tool to build healthier, more financially sound, and more attractive places to live and do business. Buses are already doing that, and their role should expand. They can provide geographic coverage and flexibility that trains cannot. That’s why buses are a key part of our Integrated Network Approach. New high-speed lines are the main trunk—but they won’t achieve their full potential without all the branches.

Getting to that point means building a culture of robust public investment in transportation infrastructure beyond highways and airports. Which means investing in, enhancing, and getting the most value of the resources we already have.

In the short-term, buses should play a major role in building a culture of leaving the car at home.

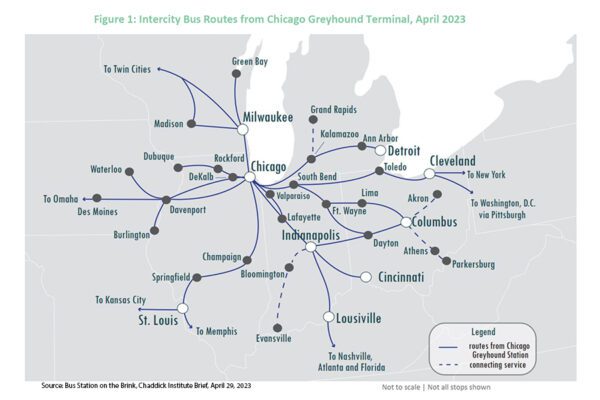

You can’t get from Chicago to Columbus (OH) by train, for example. And in a heavily-traveled corridor like Chicago to Indianapolis, Amtrak offers service just three days each week—a single run that arrives near midnight. By contrast, FlixBus/Greyhound offers around 10 trips each day, scattered throughout the day.

Here’s why immediate action is needed.

In 2021, the previous owner of Greyhound split the company into an operating unit and a real estate unit. FlixBus bought the bus operations. A private-equity firm, Twenty Lake Holdings, bought nearly all of Greyhound’s real estate. Now, the station sites are being sold for redevelopment. Cleveland has already lost the battle. Sadly, its beautiful art-deco station is slated to become the lobby of a dual-high-rise.

Before owning Greyhound, FlixBus relied on the low-cost curbside model. It may be that they planned on converting Greyhound to that model. But it doesn’t work at scale, it’s a terrible option for the city, and Chicago has a unique role as the hub of the national bus network, with a large portion of passengers waiting hours for a connecting bus.

So, the Greyhound terminal remains a vital link in Chicago’s transportation system. It currently handles 55 buses each day, taking riders to destinations all across the region. If it were a publicly owned facility and open to all bus lines (instead of just Greyhound/Flixbus and its partners), it could handle many more.

Roughly 500,000 passengers already use it each year. That’s more than many publicly-owned and subsidized regional airports—and bus stations have a vastly smaller footprint than they do. Buses also serve a distinct customer base. Riders are younger, lower-income, less likely to have access to a car, more likely to have a disability, and more likely to travel alone than the general population. Most use it for personal reasons like visiting friends and family or getting to medical appointments.

Roughly 500,000 passengers already use it each year. That’s more than many publicly-owned and subsidized regional airports—and bus stations have a vastly smaller footprint than they do. Buses also serve a distinct customer base. Riders are younger, lower-income, less likely to have access to a car, more likely to have a disability, and more likely to travel alone than the general population. Most use it for personal reasons like visiting friends and family or getting to medical appointments.

In other words, buses play a critical role in the lives of a broad population that relies on them to move around. Guaranteeing easy access to a safe, convenient station is the least Chicago can do to support them. Not offering that would make Chicago an outlier among peer cities. New York, L.A., D.C., and Denver, for example, have publicly accessible bus depots near their city centers. Atlanta and Detroit are building one with support from their state DOTs.

And this is a facility that can’t be easily replaced. Though not perfectly located, there are no better options, and it’s just one block from the CTA Blue Line, a couple of blocks from Union Station, and within walking distance to the La Salle Street and Ogilvie stations. Building a new station, in a lesser location, will cost more than just buying the existing building.

Some creativity and resourcefulness will go a long way here. The city (or state) should buy the facility, renovate it, and hire a professional management company to run it. Airports have perfected the model of becoming hubs of commerce. There’s no reason a bus terminal generating more traffic than many airports couldn’t integrate elements of that model, albeit on a smaller scale, and become a neighborhood hub adding value far beyond the status quo.

A renovated station could be a win for everyone: For the bus lines and their customers. For the neighborhood. For the city and state. Even for people who want better trains in this region.

But Mayor Johnson and Governor Pritzker will have to act quickly to ensure its future.