Engineering Firm Chosen to Design Critical High-Speed Rail Segment in California HDR has been awarded a five-year contract to deliver engineering and design services for a 54-mile segment between Palmdale and Victorville. This is a critical connection between...

Guest post by Caleb Villamin

What is the Shinkansen?

The new trunkline

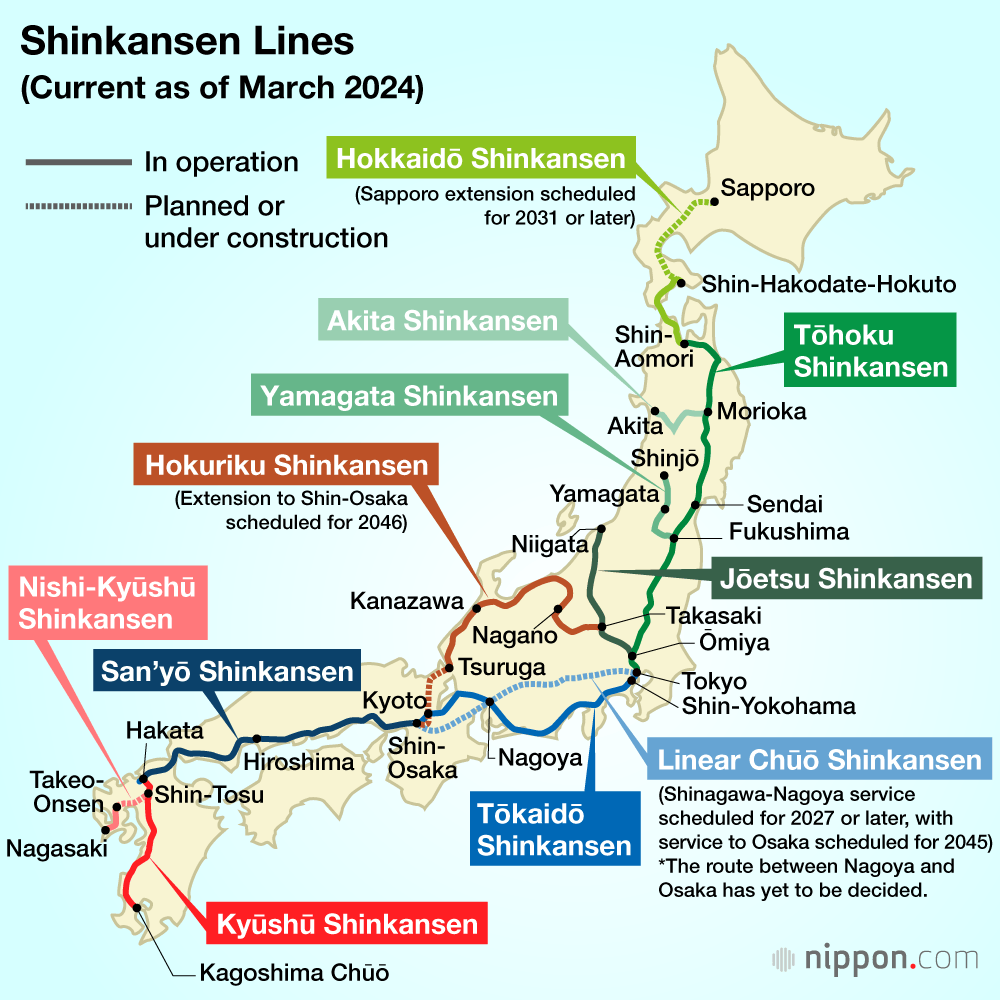

Translating to “new trunk line” from Japanese, the Shinkansen is Japan’s high speed rail network connecting many major cities and population centres across the country. First opening in 1964 for the Tokyo Olympics, the system heralded Japan’s emergence as a restored and booming economy, inspiring many other countries to create their own high-speed railways. France’s TGV, Germany’s ICE, and Spain’s AVE, all owe their existence to Japan’s groundbreaking project. Ever since its inauguration, the Shinkansen has expanded enormously to 9 lines and over 2,951.3 km (1,833.9 mi) of track, stretching all across Japan, transporting passengers quickly, efficiently, and comfortably.

A “Nozomi” high-speed express passes by a local station on the Tokyo – Osaka “New Truck Line”

The success of the Tokyo – Osaka high-speed line led to a national high-speed rail plan.

Humble beginnings in a post-war Japan

After their defeat by the allies in 1945, Japan found herself in a tough spot. Tokyo had been reduced to rubble and the economy had taken a massive beating. Social and economic revitalisation was underway from the late 1940s and 1950s in an effort to restore the livelihoods of Japan’s population. In 1958, to showcase and celebrate her progress, Japan announced that Tokyo would host the Olympics in 1964. However, there was one slight issue: traffic. With money being spent sparingly on rebuilding houses and industry, the government strayed away from investing heavily into the kinds of roadways and automobile infrastructure that was dominating the western world. The complex mountainous geography also made building intercity motorways ludicrously expensive and difficult. With Tokyo and Osaka, Japan’s two largest cities by population at the time, experiencing record-high traffic congestion due to the dense city development, the government sought alternative methods of transport. Enter the Shinkansen.

Project Scope

In 1959, the Japanese government had committed ¥200,00,000 (US$1.3B) to the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, an entirely new 515 km (320 miles) railway running from Tokyo to Osaka.

Hideo Shima, the project’s chief engineer, and Shinji Sogō, the president of Japan’s national railways, had a tall order to fulfil. The ambitious plan called for the creation and innovation of trains that could comfortably run faster than 200 km/h (125 mph) and reduce journey times between the two cities by more than 50%.

At the time, many local and international spectators saw the project as pointless. The West had committed to funding motorways and airport expansions, convinced that the humble train had been made obsolete. To prove them wrong, engineers reimagined what a train and railway was in numerous ways:

- Tunnelling through 108 km (67.11 mi) of mountains to avoid sharp curves and maximise speed

- Eliminating the use of locomotives – distributing power to all wheels to avoid rail degradation

- Using automated train control (ATC) signalling to increase reliability, safety, and frequency

- Using lightweight materials and an aerodynamic design

- Switching from the Japanese narrow gauge to the wider international standard gauge tracks for stability

A Series 0 Shinkansen in the JR Central Museum in Nagoya with the ribbons celebrating its launch in the background.

The opening ceremony on October 1, 1964.

Successes

The effort paid off.

On the 1st of October, 1964, the inaugural service of the Shinkansen began with much fanfare. Hundreds had gathered in Osaka and Tokyo to witness the first trains arriving. True to the engineers’ word, the train sets reached a top speed of 220 km/h (137mph), reducing the travel time between the two cities from 7 hours by existing railway to a mere 3 hours and 10 minutes. Japan had created the world’s first high-speed rail line, and it was a massive success. Within the first three years of operation, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen saw over 100M passengers. Wanting to capitalise on their successful service, the Japanese government began to draw up plans for an extension south of Osaka to Fukuoka, which opened in 1975. It’s opening meant that, one could travel the 1,094 km (680 mi) from Tokyo to Fukuoka in just about 5 hours. Since then, further extensions have been built, with a current total of 9 Shinkansen lines connecting cities and regions all across Japan.

Impacts on Japanese Society

The presence of the Shinkansen caused a seismic shift in Japanese society’s behavior.

For instance, the reduced travel times allowed for people to spend more time at their destination, and thus increased consumption of local goods and services. The Japanese government sites that the expansion of “range of activities” enlarged the commutable area, increased tourism, and heightened the value of real-estate assets. Land near Shinkansen stations shot up in value, spurring the establishment of shops, restaurants, and services in and around them. In the modern day, many Shinkansen stations have integrated shopping centres inside to better serve travellers. For example, Kyoto’s massive station is home to 130 shops and restaurants. Additionally, the abundance of businesses near Shinkansen stations helps recapture operating costs, similar to the model well-known by Hong Kong’s MTR metro system.

The Kyoto Railway Station is a busy economic hub with shopping, a major hotel, and public gathering spaces.

The Kyoto Railway Station is a busy economic hub with shopping, a major hotel, and public gathering spaces.

The bullet train also changed how populations were distributed.

Since commuting longer distances within a shorter time became possible, people no longer needed to live within the city centre to work and access services. This led to the development of large, dense residential areas outside city centres. A prime example of this is with Shizuoka, a city located 173.3km (107.7 miles) west of Tokyo, which saw a development boom after the construction of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen in 1964. With the population spreading out, housing costs within large cities were relieved. Jerry Nickelsburg of UCLA states that the Shinkansen relieved “congestion and home price pressure in Japan’s largest cities to a certain extent”. Tokyo, for instance, sees an average monthly rent for a 1-bedroom apartment of US$711.0 (Statista Research Department, 2023), despite being the world’s largest city by population.

Wealth and prosperity

Finally, the Shinkansen has brought wealth and prosperity to cities and regions connected by the service. Kyushu, a city 1,200 km (746 mil) south of Tokyo, generated JP¥46B (US$ 295M) after the Shinkansen was extended there in 2011. Due to the positive effect the system has on businesses, tourists, and wealth, many politicians court extensions to their local regions, according to Japanese railway and political scholar Takashi Hara. That is in huge contrast to politicians in the U.S and Canada, who constantly reject rail transportation plans.

The Shinkansen has increased prosperity by making travel easier, faster, and less expensive.

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!