Cleveland wants to reinvent its downtown and lakefront. Great trains are the critical missing piece.

Key takeaway: Local civic and business leaders should work with the governor’s office, the legislature, and the Ohio Department of Transportation to establish great train service from Chicago to New York, via Cleveland, as part of the city’s bid to reinvent its downtown through the “Shore-to-Core-to-Shore” initiative.

70 million people within 250 miles

Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame draws more than half a million visitors each year and has an estimated annual impact of $250 million. It’s regularly named one of the nation’s best museums. And a $135 million expansion is scheduled to open late next year. Love it or hate it, it’s a pillar of the city’s economy.

But here’s a weird fact about the Rock Hall of Fame.

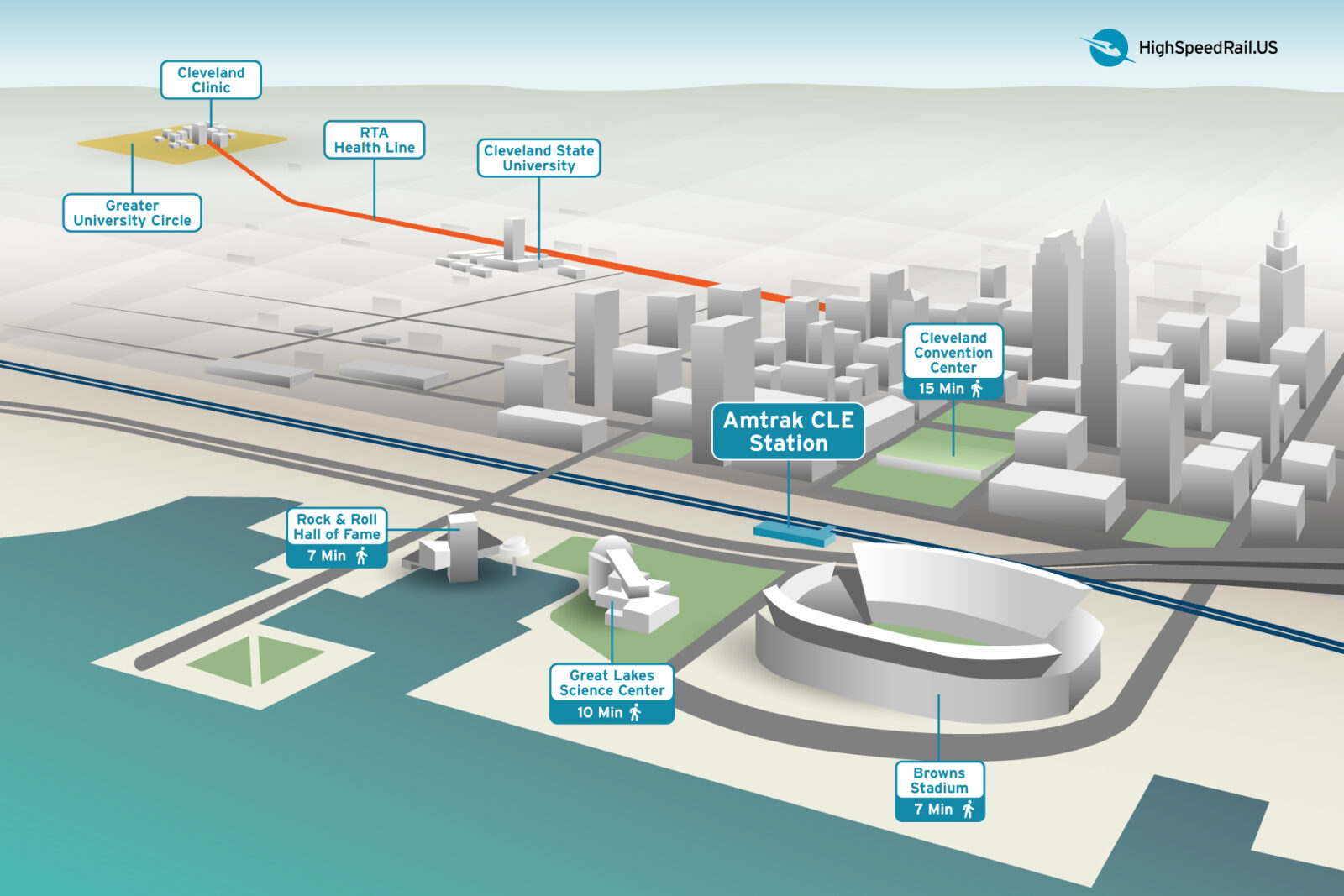

Roughly 70 million people live within 350 miles of the Cleveland metro area, and about 80 percent of the Rock Hall’s visitors arrive from outside of Cleveland. Yet it is nearly impossible to get there by train—even though it sits right next to Cleveland’s Amtrak station. The station offers just four daily departures – in the middle of the night.

Why does this bare-bones service matter—aside from the fact that trains are safer than driving, more affordable than flying, and faster (plus vastly better for the environment) than both?

One answer is that it should be a no-brainer to make a pillar of your city’s economy more accessible to tens of millions of people—especially since great train service would boost attendance at other local institutions. For example, the Great Lakes Science Center is right next to the Rock Hall. And the Children’s Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the home of the Cleveland Orchestra are nearby. Fast, frequent train service in Cleveland would benefit all of them.

But boosting tourism isn’t mainly what great train service is all about. It’s about making Cleveland a better city to work, play, and build a business in.

Because that’s what trains do. They create cities where people want to be—for the long haul. Places full of creativity and life. Cities with a good mix of residents, small businesses, corporations, and nonprofits. Cities whose design and infrastructure bring people together instead of pulling them apart. Cities with strong cores.

Cleveland’s ongoing “Shore-to-Core-to-Shore” initiative has exactly that goal. Which is why this the perfect time for train advocates and local business leaders to step up, make the case for great train service in Cleveland, and push for it. A good first step would be to contact state representatives here.

Reimagining and rebuilding Cleveland’s core

Unfortunately, six decades of highway proliferation have steadily hollowed out Cleveland’s downtown. In fact, a new study analyzing the effects of road construction in US cities found Cleveland ranked first—which is to say, worst—in terms of the divisions and social isolation created by highways.

Trains are the tool that Cleveland needs to repair this damage and rebuild its core. Consider that a single lane of interstate carries about 3,000 travelers an hour—but only in good weather and with no accidents or congestion to slow things down. By contrast, a single, high-speed-rail track with roughly the same footprint can safely carry upwards of 12,000 passengers an hour (even in bad weather). And it can deliver them right to the heart of downtown instead of airports and parking garages.

What happens when more people begin arriving regularly in downtown train stations?

What happens is a whole lot of economic exchange. People visit their primary destination and then walk, scooter, bike, taxi, or take transit to nearby stores, bars, restaurants, and museums. The effects ripple out across the city and create a virtuous cycle of wealth-building.

That’s wealth-building in the broadest sense. It’s not just that trains boost nearby property values. That happens, but it’s important to be clear about cause and effect. Property values increase—and economies grow—because trains bring people together, transform acres of parking lots into places of life, and create wealth and real value rooted in community values.

Building the healthcare and education sectors

Trains will develop Cleveland’s core strength, as well, by building on its competitive advantages in key sectors like healthcare and education.

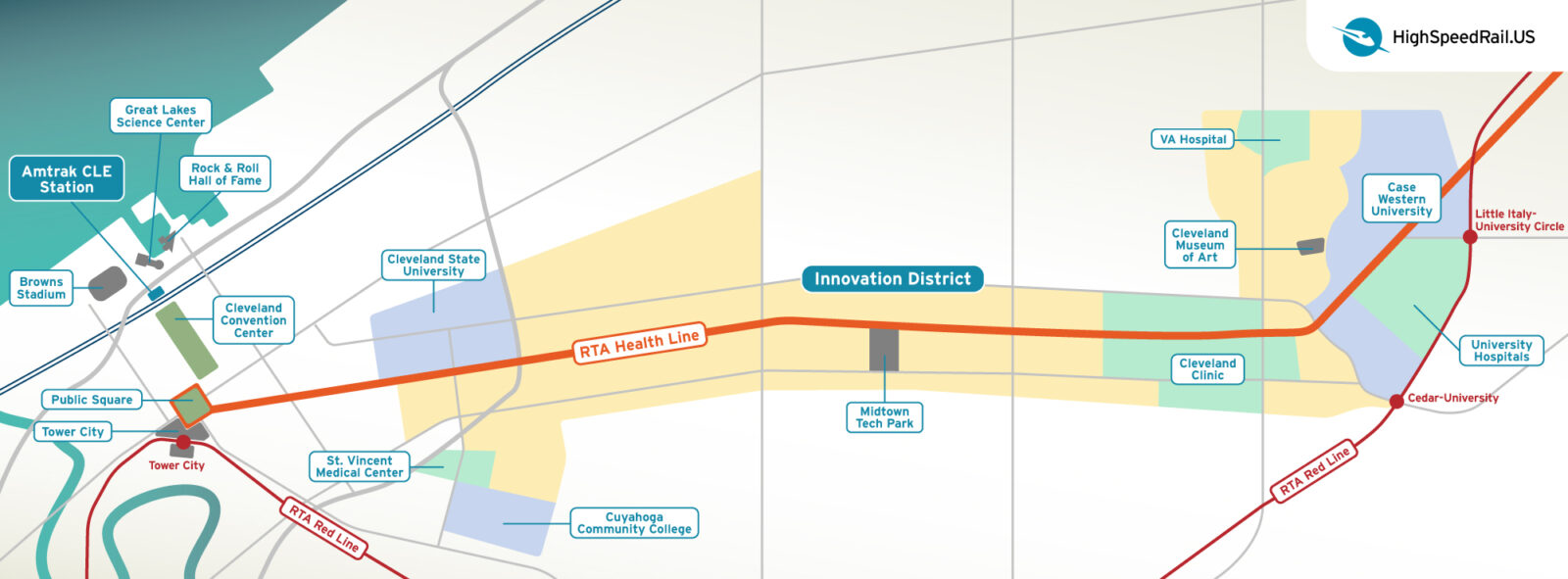

Consider the city’s “health-tech corridor,” which stretches east from downtown to the University Circle neighborhood. It’s home to several of the city’s cornerstone institutions, including Cleveland State University, a public university serving about 16,000 students; Case Western Reserve University, a prestigious private university with several Nobel laureates on the faculty; Cleveland Clinic, a world-renowned hospital serving more than 3 million people from around the world each year; and University Hospitals, the largest biomedical research center in Ohio.

The Cleveland Clinic alone supported about $28 billion to Ohio’s economy in 2023. (Ohio’s total GDPis about $640 billion.) Cleveland Clinic is also the state’s largest employer, and it’s part of a pioneering movement that pushes for healthcare systems to be transformative, community-building forces by buying and investing locally.

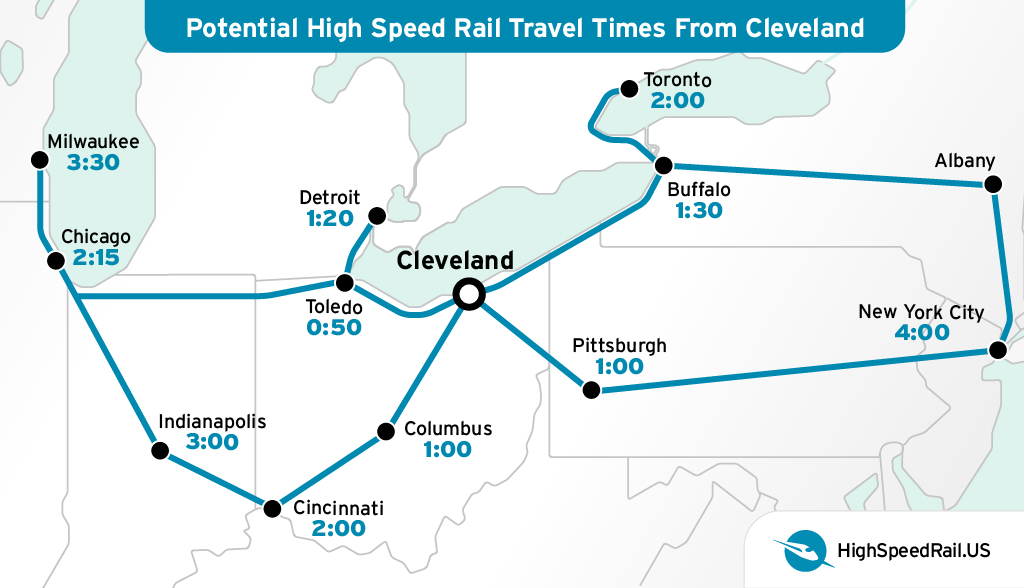

So the pieces are in place for Cleveland to be a world-class health-tech hub. And Cleveland has the kind of strategic location that most cities can only dream of. It’s the midpoint of an east-west corridor that stretches from Chicago to New York, and it’s the apex of a triangle anchored by Pittsburgh and Columbus. Collectively, these corridors are home to some of the nation’s most innovative institutions, including many in the education and health-tech sectors.

They offer prime opportunities for collaborations and partnerships—in sectors where cross-institutional collaboration is especially fruitful and valuable. Yet the current transportation paradigm undercuts that potential. Most of Cleveland’s regional neighbors, after all, are too close for a flight to make sense but too far away for an easy drive.

With true high-speed rail service, they could be a short, pleasant train ride away: 80 minutes to Detroit; 90 minutes to Buffalo; and about an hour to Pittsburgh and Columbus. Even high-quality conventional trains could easily beat flight times (factoring in security check and wait times at airports). And all trains—high-speed and conventional—boost productivity by giving riders a comfortable space where they can work, rest, or socialize instead of fighting traffic.

In short, fast, frequent train service will make regional collaborations much easier. Which will create a stronger health-tech sector in Cleveland. Which will help build the strong and resilient core that’s vital to Cleveland’s overall vitality and growth.

The power of trains, verified

This isn’t just speculation. There’s actual data on it.

China’s massive investments in high-speed rail over the past two decades, for example, have provided plenty of opportunities to study the economic and social effects of HSR.

One study focused on the question of whether HSR improved “urban livability.” It found that it did, in three concrete ways: by promoting economic growth, talent agglomeration, and industrial structure upgrading. In other words, HSR boosts investment in the buildings where people work and make things. And it brings more skilled workers into closer contact in urban spaces. The result is strong economic growth.

Another study found that “economic growth in cities with operational high-speed lines was significantly higher than those without high-speed rail.” The effect was particularly strong in bigger cities, “highlighting their stronger ability for economic agglomeration and growth potential.”

These studies focus on the impacts of high-speed rail, but the effects hold true for fast, frequent conventional trains as well. And that would be a great place for Cleveland to start—i.e., pushing for faster, more frequent service on the two Amtrak lines that now barely serve the city.

One of those routes—the Lake Shore Limited—runs from New York to Chicago and is one of the most promising corridors in the nation for a high-speed line. Which means Cleveland should be a strong champion for getting one underway.

In the meantime, better conventional train service would pay big dividends. Four daily, Lake Shore Limited roundtrips would be a great start, offering a base level of service at key travel times.

The business community is key

Medium- and long-term planning around train service should be much more ambitious.

Cleveland’s economy is critical to the health of Ohio’s economy, so it should be a top state-level priority. Gov. Mike DeWine and the legislature should get behind serious studies of adding Amtrak frequencies from Cleveland to Chicago, Detroit, and New York. They should also work with Congress to put expanding the Chicago-New York and Chicago-D.C. lines at the top of Amtrak’s agenda. Fast, frequent, and affordable trains in those corridors will be game-changing for Cleveland as well as Ohio.

For its part, Cleveland is pursuing a “Shore-to-Core-to-Shore” initiative designed to connect its downtown more closely with its lakefront and riverfront. One proposed project—the North Coast Connector—is a land bridge over the highways and railroads that currently divide downtown from the lake. The bridge “will link Downtown Cleveland’s central business district with a lakefront redesigned with park facilities” and various other public spaces, Cleveland Magazine notes. Plans for the lakefront also include a new multimodal transportation center for buses and trains.

This is a big step in the right direction. But what’s missing is a vision and a push for the level of fast, frequent train service that would be genuinely transformative for Cleveland’s downtown and lakefront.

So this is the moment for local champions to step up. Construction on the North Coast Connector is set to begin in 2027, which means there is strong momentum to build on. And, as the Cleveland Citywide Development Corporation notes, there are at least 26 organizations “dedicated to improving business in the City of Cleveland.”

Nothing will boost the business environment in Cleveland like great train service. And nothing can move the needle on that goal like the city’s business community pushing leaders in Cleveland—and in the state legislature—to make great trains a top priority.

That hasn’t happened yet. The good news is that there are immense opportunities right on Cleveland’s lakefront, waiting to be seized. Great trains will make Cleveland an even better place to work, play, and build a business. And they will integrate perfectly with plans the city is already pursuing for the lakefront.

There’s a way. Is there the will?