Advocates must keep up pressure to help him deliver on promise. Illinois legislators will return to Springfield Oct. 14 for the Veto Session, at which they also can take up urgent legislation that they did not pass in the spring. Such a piece of legislation is the...

How We Connect Lines and Connect Regions

Highways and airports connect the whole country.

We need to think just as big about creating regional and national high speed rail connections. That’s what an integrated approach to high speed rail is.

A national program helps connect local, regional, and interregional routes. It’s a comprehensive vision that starts at your local station and extends across the country.

Everyone will benefit from faster trains, but without the big-picture network view, it is hard to coordinate all the stakeholders. An integrated approach changes that, and gets us closer to having national connections.

Trains are Fast and Cost-Effective For Every Distance

There is a common myth about travel.

Any trip fewer than 100 miles is for driving, anything more than 500 is for flying. Trains only work in that middle-ground.

But that doesn’t have to be true. When you have local, regional, and inter-regional trains connected, you can travel quickly anywhere.

Through cities. Through the suburbs. Across rural areas. Across the country.

That means less waiting in traffic. It avoids the frustrations of airports. It’s comfortable, fast, and easy.

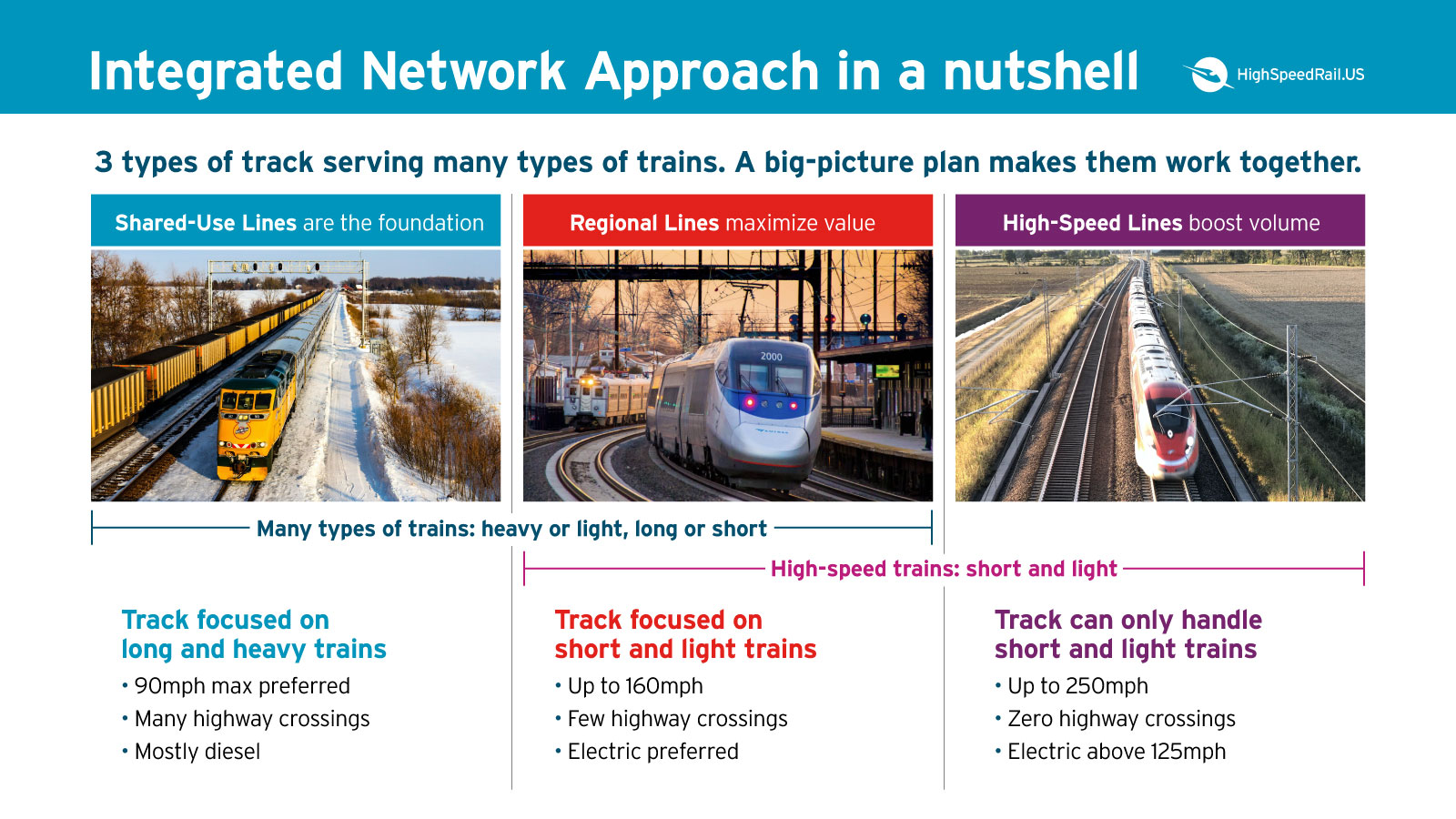

Better Tracks, Better Trains and a Big-Picture Plan

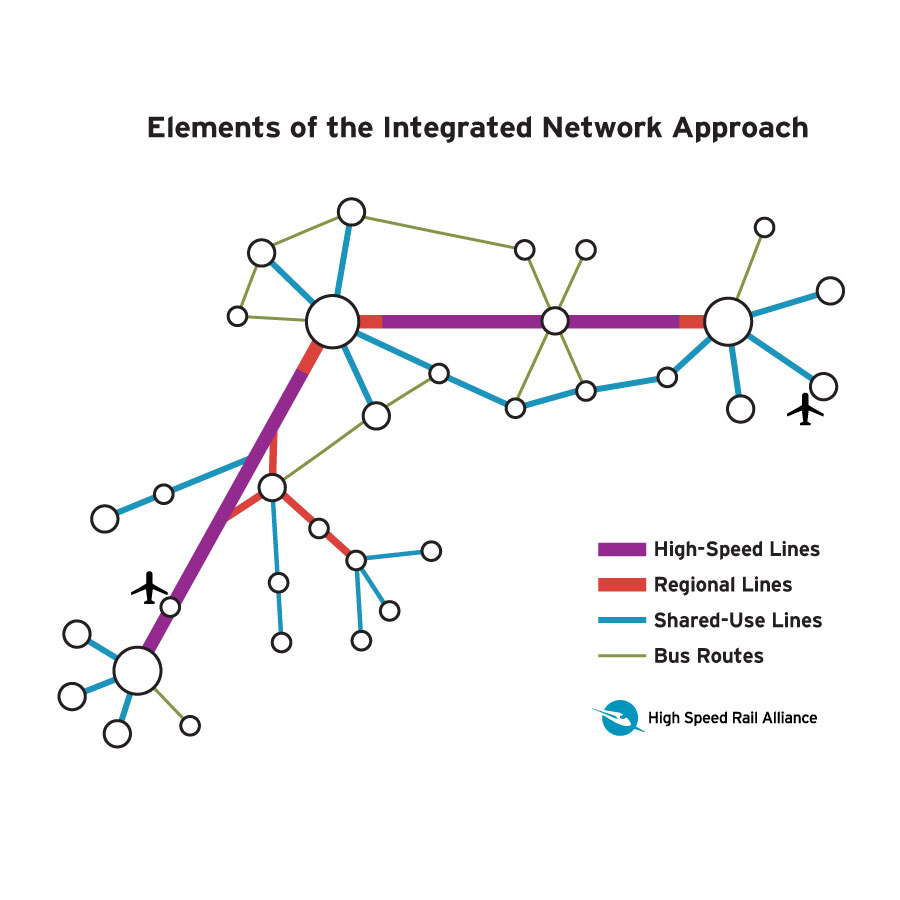

The Integrated Network Approach connects entire regions by combining the transformative power of dedicated high-speed lines with the geographic coverage of tracks that handle both passenger and freight trains.

Used across the world, it delivers steady and incremental progress, guided by a long-term plan.

New segments of new or upgraded lines are steadily added over time, like building blocks, to create a growing and thriving network.

In some cases, high-speed trains run on both high-speed and shared-use tracks. In other cases, passengers easily switch between high-speed and conventional trains to get to their destination.

This approach fuses multiple types of trains—running on different kinds of tracks—into a single, flourishing, high-volume network.

In the process, it builds popular support for trains of all kinds.

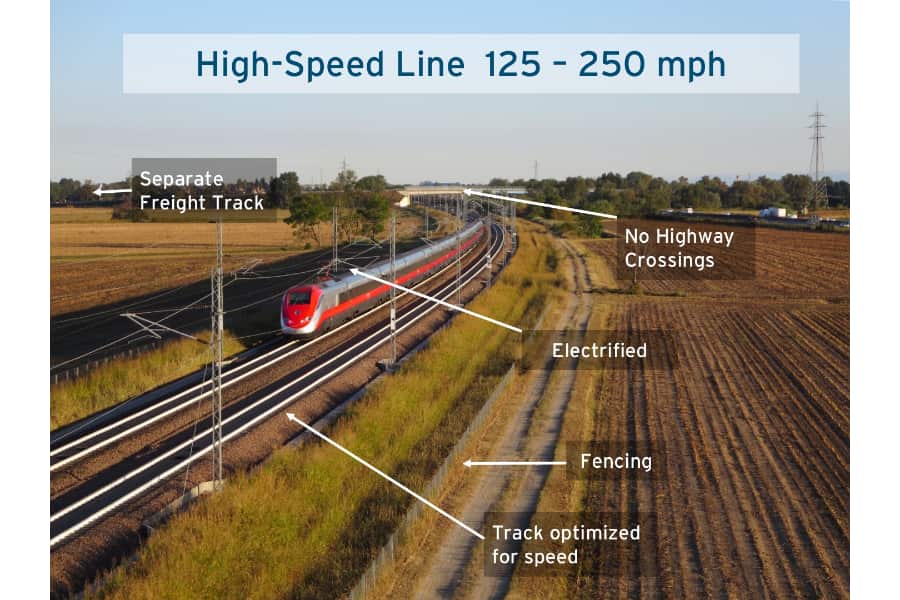

The Milan – Bologna high-speed line was built alongside the Autostrada.

High Speed Tracks: The Backbone of the System

Between slower regional lines and shared-use lines are actual high-speed lines.

These connect the branches of the integrated rail network, allowing for fast and easy travel.

How fast? Up to 220 mph, much faster than America’s fastest passenger trains. This makes traveling long distances even easier and more convenient. What does this entail?

- Dedicated tracks

- Elimination of grade crossings

- Overhead power

High speed rail can be done. The integrated network can be built. It all starts on the ground.

Help Us Connect. Get Involved In the High Speed Rail Alliance

To move forward, we all have to move together. Join like-minded people and make a better tomorrow. Together, we can make high speed rail a reality in your region.

Common Myths About Integrated Rail

Myth: High Speed Rail is just for big cities

Virtually any area can be connected to a high speed rail system. Local lines can connect to high-speed lines, bringing everyone into a quick and easy way to get around.

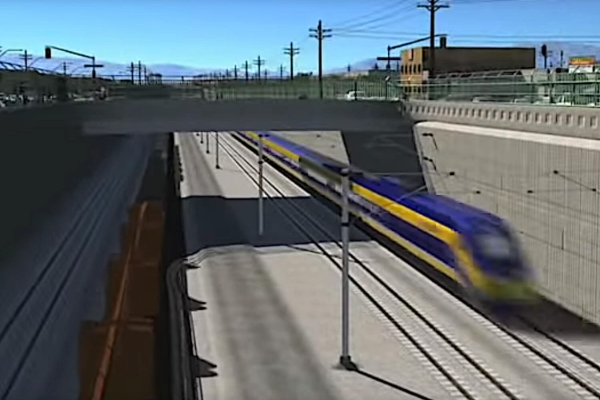

Myth: We have to cut new rights-of-way through cities

High speed trains can be run on upgraded, existing train lines, meaning there is no need to establish new rights-of-way in cities.

Myth: We have to choose between building new and fixing what we have

A large network plan leverages upgraded, existing infrastructure to get rolling, and adds segments of new high-speed line to boost the system. We don’t have to build it all from scratch.

How Do We Get There?

What needs to happen to truly have an integrated network approach to high speed rail?

Big thinking. Big planning. And a lot of details. That means:

- Thinking about networks, not just short routes between cities

- Thinking about being inclusive for everyone

- Thinking about coordinating between different agencies

- Thinking about being flexible for different train lines

- Thinking about a long-term plan

It’s time to think big. It’s time to think about an integrated approach.

Read how California is Pioneering the Integrated Network Approach

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!