Please ask your senators and representative to support American manufacturing capacity for new trainsets For too long, the United States has neglected the potential of passenger rail. As a result, Amtrak has an aging and shrinking fleet. The national passenger...

Departments of transportation at all levels need to plan passenger-rail systems in broad networks, rather than individual routes. This is radically different than highway and airport planning, where a robust network already exists. Their planning focuses on facilities, with little attention to network impact.

Highway planning is centered on building a segment of road that will be available to all users. The overall roadway network is already in place, and there is little consideration for how the network functions. While there may be detailed traffic counts for each segment, there is no real information on where people are traveling to and from and no information on why. Planning models assume that demand will continue to grow and that funds will be available for construction.

The highway policy framework is fairly simple: the owner of the road is responsible for planning, construction, and maintenance. If federal funds are involved, there is a clear procedure for obtaining those funds, most of which are allocated to the states by formula. Very little consideration is given to the ongoing budget impact of maintaining the road.

Similarly, there is little network planning for the aviation system. Individual municipalities or authorities plan, finance, construct, and maintain local airports with Federal Aviation Administration involvement. There is a clear procedure for gaining federal funds and planning models assume continued growth of demand. The local government builds the biggest facility it can and then sells terminal space to airlines.

The result is that there is little experience to support transportation planners thinking about passenger-rail systems as networks.

Splintered passenger rail planning and funding

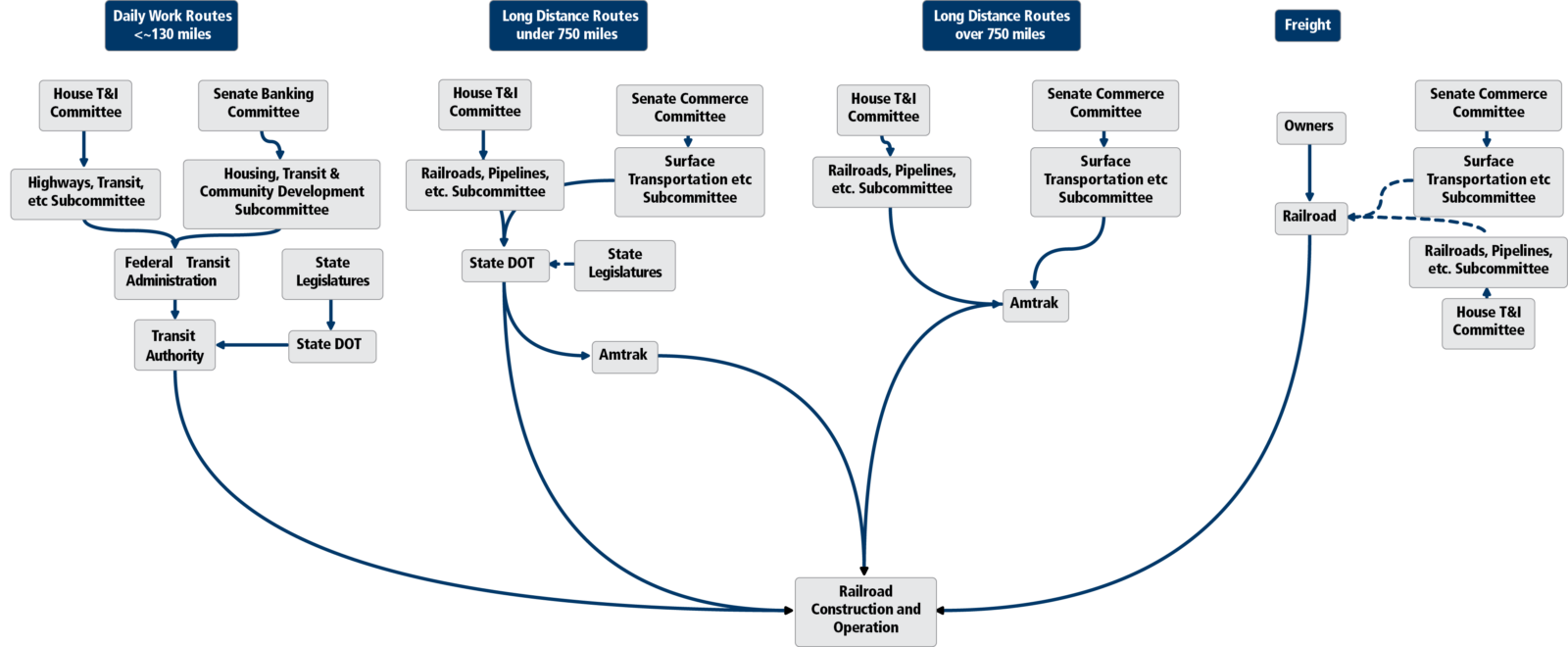

Another problem with current railroad planning is that it revolves around five service categories :

- daily work commutes

- intercity trips under 750 miles

- intercity trips over 750 miles

- freight

- Northeast Corridor

Each has been assigned different objectives. As the diagram above for the first four shows, the planning process, demand forecasting, and money flows are separate and complicated. Furthermore, the planning process uses demand models that often ignore the multiple uses for any single train. The planning process also assumes very conservative demand growth and that little funding will be available.

Commuter railroads are focused on journeys to a major center in the peak period. This category represents a small share of all trips throughout a region. Additionally, since they are often funded in part by local taxes, they may stop short of an important city in an adjoining, but separate, tax district. For example, Metra’s UP West line terminates in Elburn, just 15 miles away from Northern Illinois University, which is outside of the county boundaries of the Regional Transportation Authority’s taxing district.

Long-distance routes under 750 miles long are funded and managed by states, except if its the Northeast Corridor, in which case it is a federal funding responsibility . This creates a big problem since most networks need to serve several states to be effective, and there are few existing legal structures allowing states to collaborate on large transportation projects. The result is that service is compromised and infrastructure projects are obstructed.

For instance, Michigan cannot fund and construct the 45-mile South-of-the-Lake Reroute through Illinois and Indiana that is critical to making Michigan trains successful.

To circumvent some obstacles, Midwest states have struck relatively informal agreements on who pays for which trains. Operations for Amtrak’s Wolverine, Blue Water, and Pere Marquette, for instance, are all paid for by the state of Michigan — even though these trains originate or terminate in Chicago. Illinois pays 100% of the cost of passenger trains from Chicago to St. Louis. Illinois and Wisconsin, meanwhile, have agreed to split the cost of the Hiawatha service between Chicago and Milwaukee, with Wisconsin picking up 75% of the tab.

Long-distance routes over 750 miles long are managed by Amtrak. Trains like the Empire Builder, the Southwest Chief, and the Lake Shore Limited are phenomenally efficient, serving many dozens of overlapping markets and providing mobility to many communities that lack airline service. However, the positive effects of the longest of long-distance routes are spread out so thinly and over so many states that is it difficult to build a constituency to support more investment.

Freight railroads are privately owned, either by shareholders or a direct owner. They are focused on long, heavy trains going long distances. They ignore the majority of the freight market — short-distance shipments that need consistent, high-frequency service.

The 36-mile segment of the BNSF line between Chicago and Aurora, Illinois, highlights the tangled state of rail planning and funding in the U.S. today. This segment of track hosts Metra commuter trains, Amtrak Illinois Carl Sandburg and Illinois Zephyr service from Chicago to Quincy, Amtrak California Zephyr and Southwest Chief long-distance trains, and the owner’s freight trains.

Some of these trains are under the supervision of the Federal Transit Administration while others are overseen by the Federal Railroad Administration. An encyclopedia of congressional committees and sub-committees set policy for these entities with very little coordination, and funding originates from multiple sources and is administered through a variety of frameworks.

This corridor works today because it was designed and constructed when a single owner, the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, was responsible for the whole package and viewed passenger trains as a valuable market. It is difficult to imagine building it today.

Dividing the railroad network this way and planning and funding rail systems through a snarl of disconnected committees and agencies makes it very difficult to build the broad-based constituency needed to gain the funding for infrastructure investments. Markets should be added together but instead are being splintered into ineffective slices.

The way the nation plans and funds railroads shouldn’t be this complicated! If you agree that the United States needs a national railway program, structured like the Interstate Highway program, please sign and share this petition.

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!