Traveling last Friday through Iowa and Illinois, an eastbound Amtrak California Zephyr showed little or no sign of being affected by the CrowdStrike glitch and the cascading computer outages that followed. A morning announcement advised travelers that the café car...

This was originally posted as a thread on X by:

Marco Chitti, @ChittiMarco

Substack: https://substack.com/@marcochitti

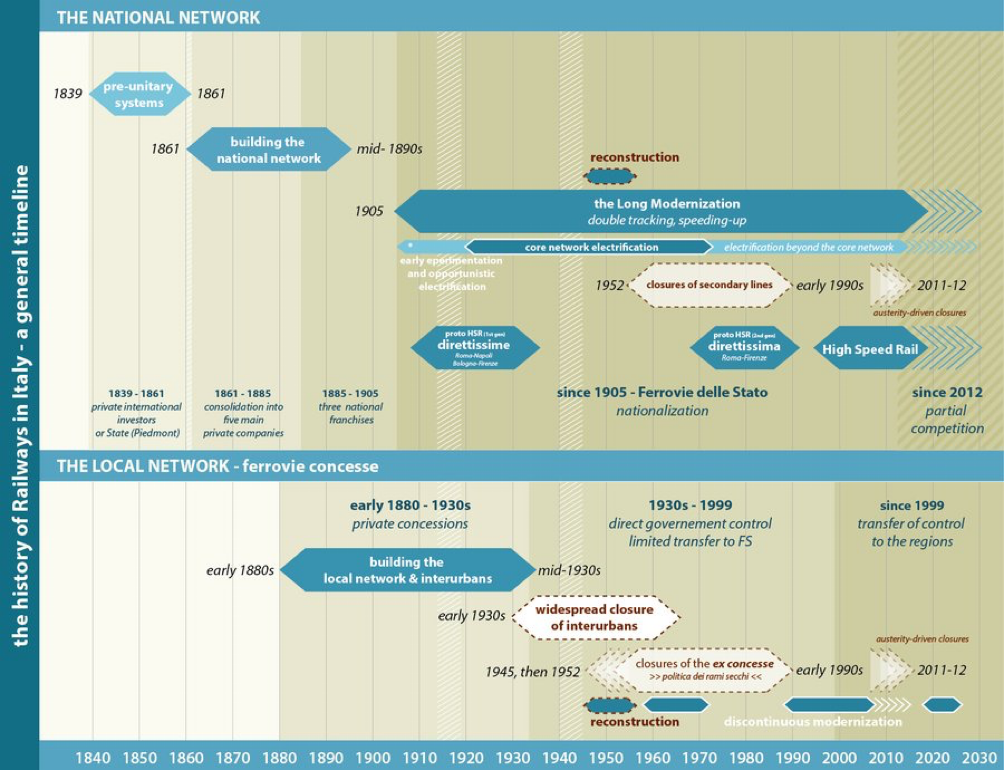

The topic is one I like to talk from time to time: railway “modernization”.

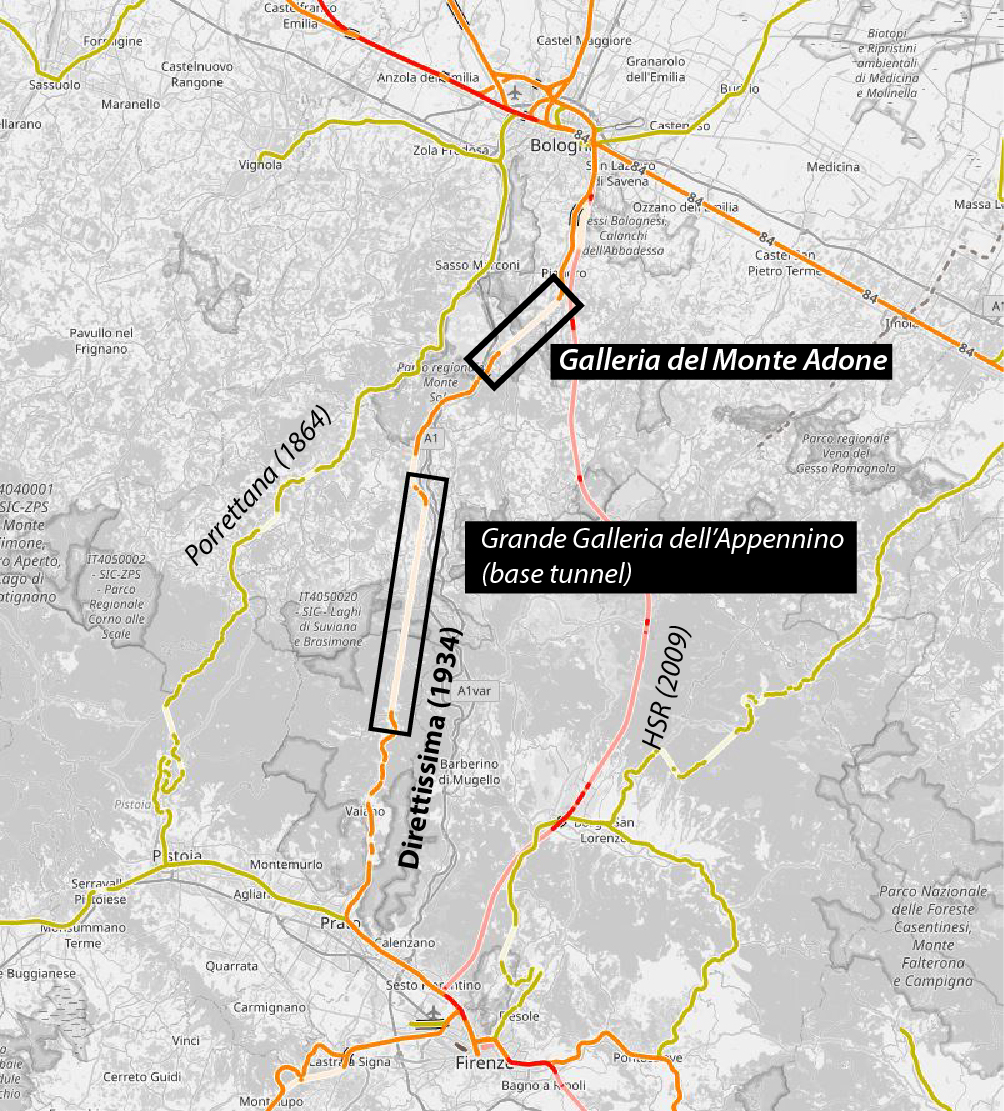

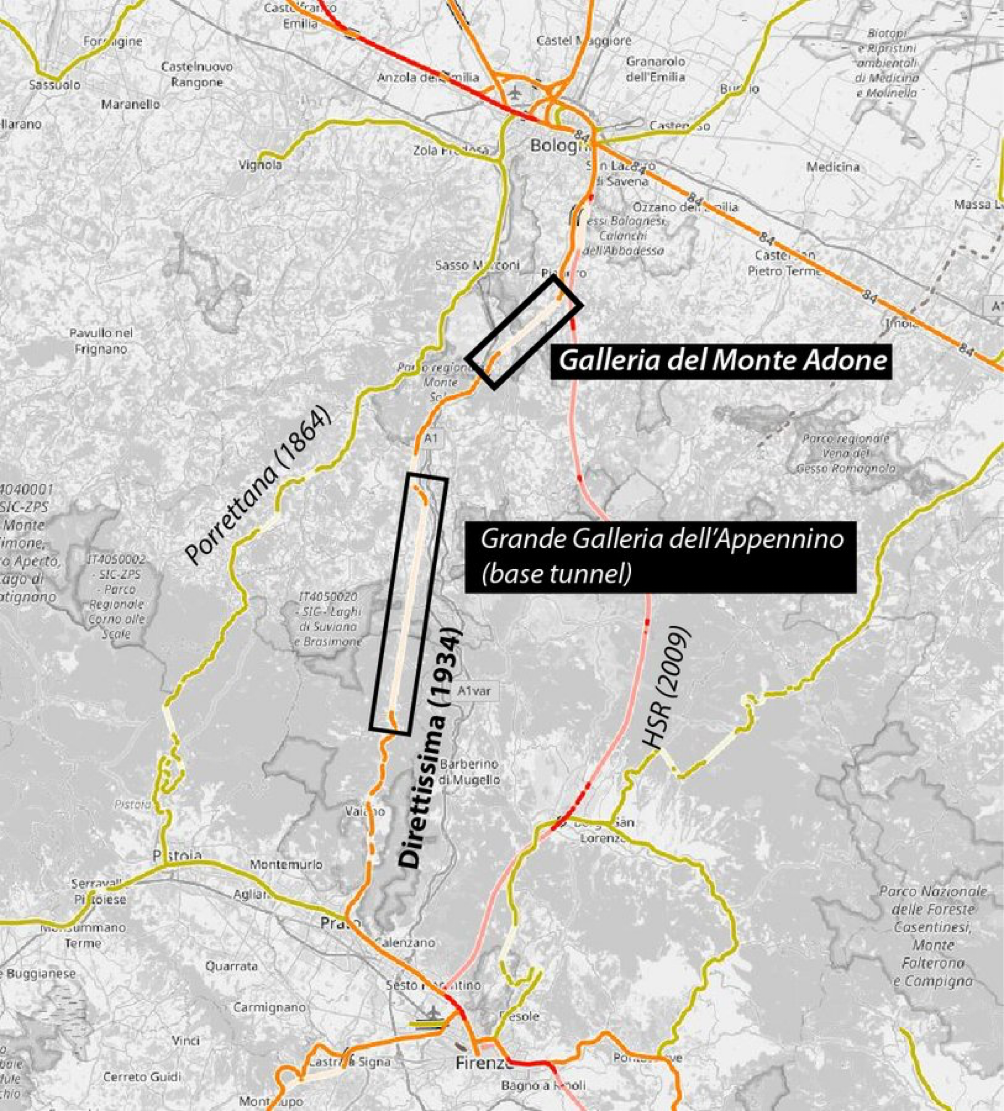

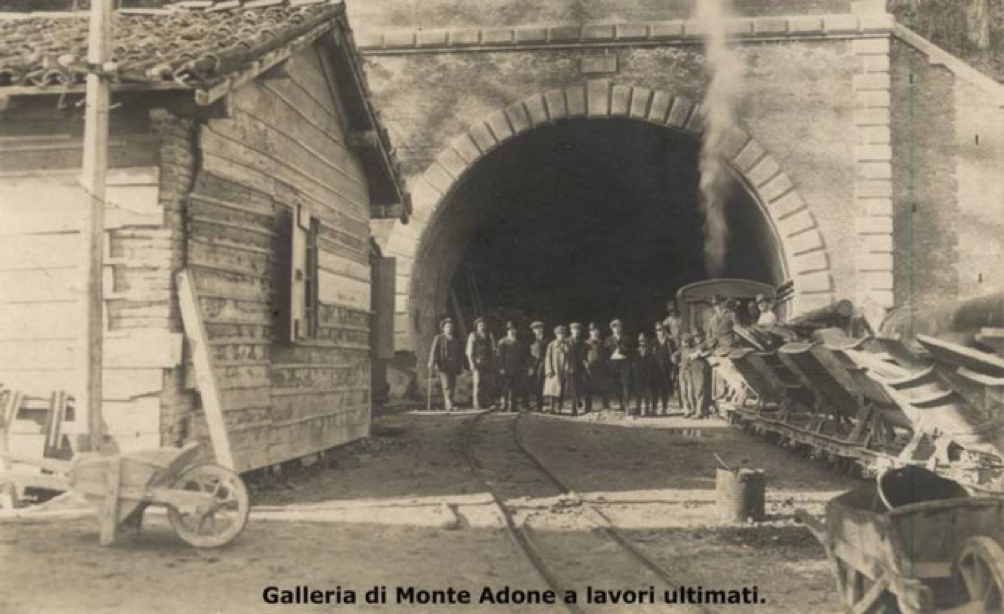

I argue that what makes the 1910-30s Direttissima Bologna-Firenze a truly “modern” rail is not its long base tunnel but rather its second longest one, the Galleria di Monte Adone.

I have already talked before about the “Direttissime”, sort of proto-HSR built in the 1910-30s as part of a broader long-term effort since nationalization to modernize the Italian railway network through electrification, new stations, double-tracking etc.

Completely grade-separated, designed for 180 km/h operations, with low grades, and electrified. These characteristics makes the Bologna-Firenze direttissima a proto-HSR, especially considering it was planned in the early 1900s and given the rough topography it goes through.

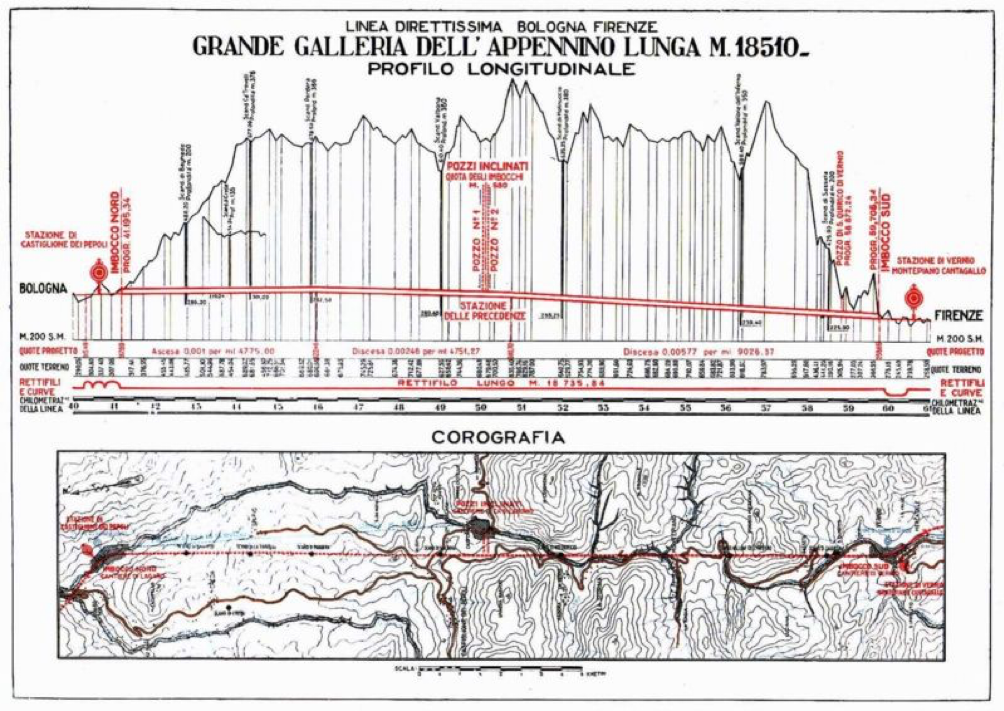

The GGA, the Grande Galleria dell’Appennino (the Great Appennine Tunnel), the line’s 18.5 km base-tunnel, gets most of the attention as the “modern feat” of that line, as it was an indeed impressive engineering effort and for a long time the world second-longest tunnel.

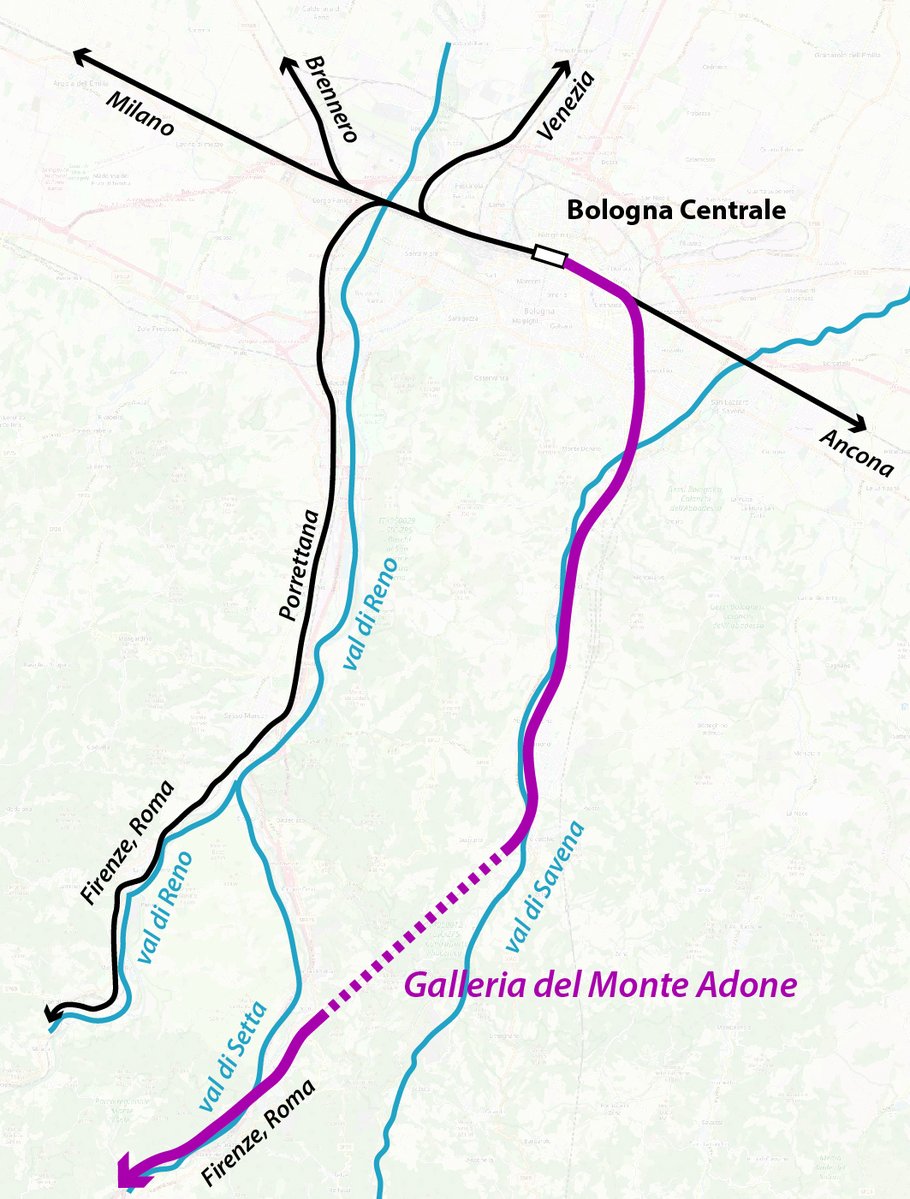

However, I think that the second-longest tunnel in the line, the 7.1 km Monte Adone tunnel is even more “modern” because it exists solely for allowing for “modern” seamless rail operations of fast long-distance trains rather than being necessary because of a given topography.

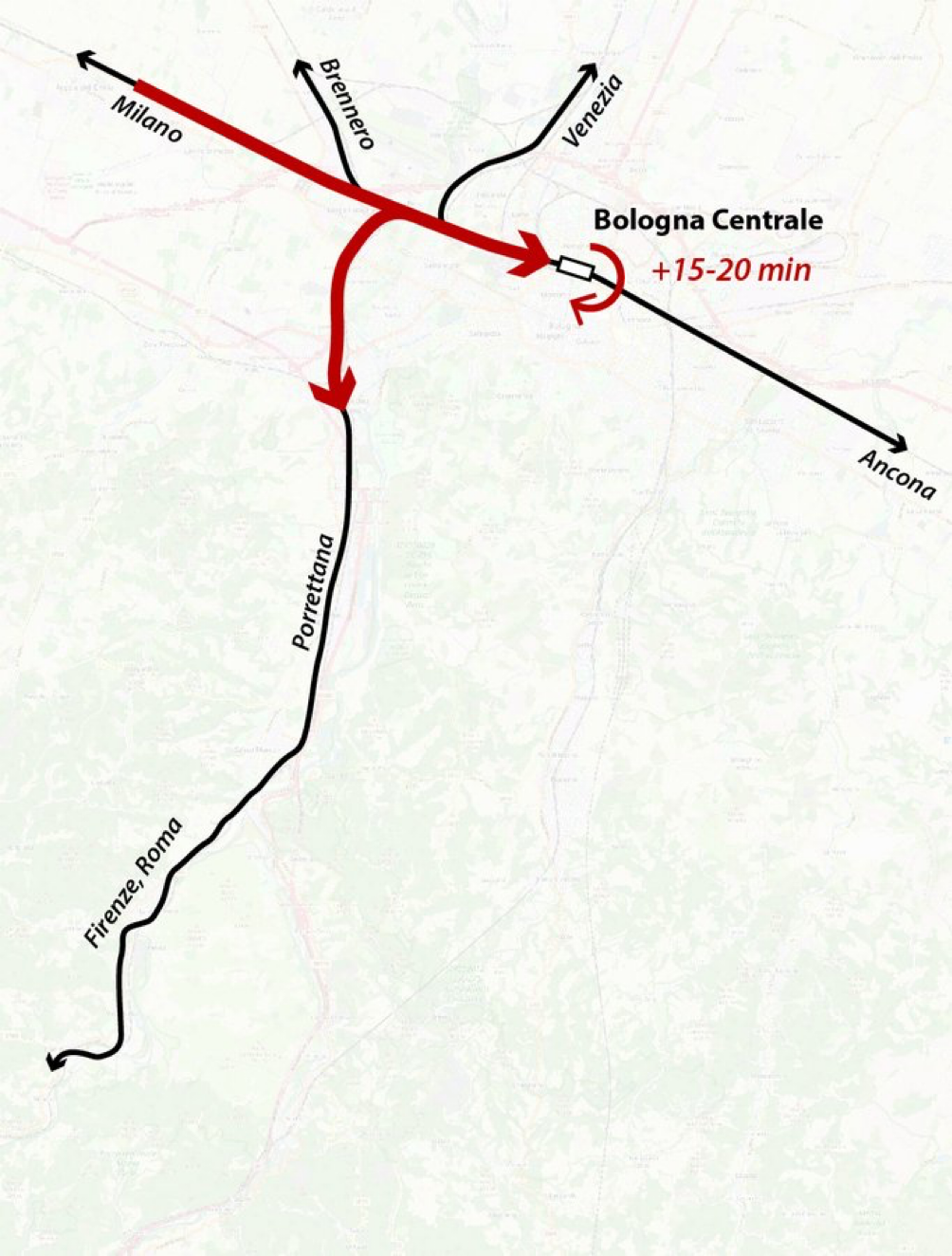

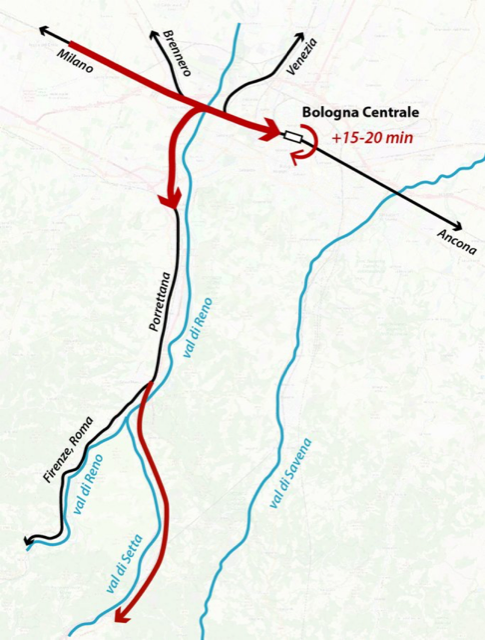

Before the the Direttissima, trains converging to Bologna from the North (from Milan, the Brenner and Venice) and continuing south to Florence and Rome via the Porrettana railway had to reverse because all these lines enter the station from the West, adding some 15-20 minutes.

When discussions started in the 1890s about building a new low-grades 2-tracks line between Bologna and Florence, the Setta Valley was considered to be the best alignment: relatively wide bottom (a rarity among the typical Apennines’s V-shaped narrow valleys), shortest base tunnel

Before the the Direttissima, trains converging to Bologna from the North (from Milan, the Brenner and Venice) and continuing south to Florence and Rome via the Porrettana railway had to reverse because all these lines enter the station from the West, adding some 15-20 minutes.

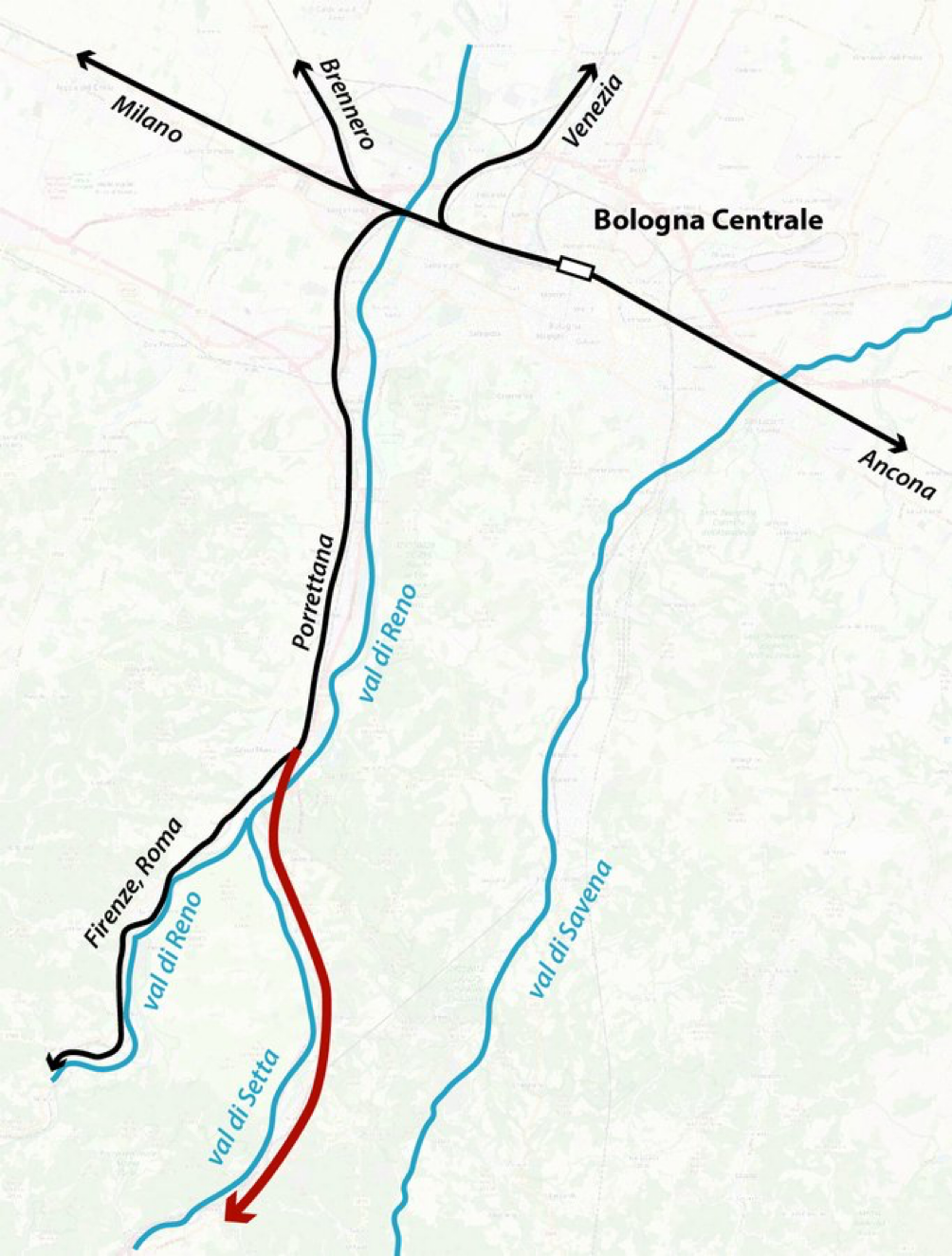

The problem is that the Setta Valley is a lateral of the Reno Valley (where the Porrettana rail is) and the cheapest and easiest alignment, branching off of the existing rail, would have meant that all the N-S trains would still need to reverse at Bologna Centrale.

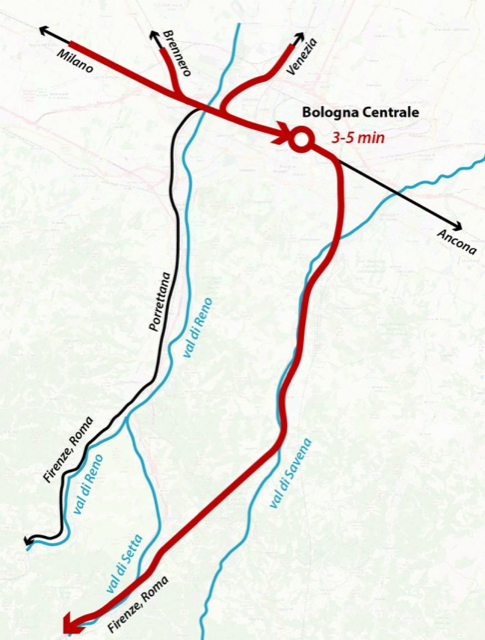

Since the very idea behind the Direttissme was to introduce very fast, non-stop intercity trains along the main corridor of the country, the final early 1900s design opted for a line heading East from Bologna C.le, then up the Savena valley and then to the Setta one via a tunnel.

From a pure “engineering route-of-least-resistance-with-regard-to-topography perspective”, the Monte Adone tunnel was absolutely gratuitous. But it wasn’t for seamless operations of N-S intercity trains

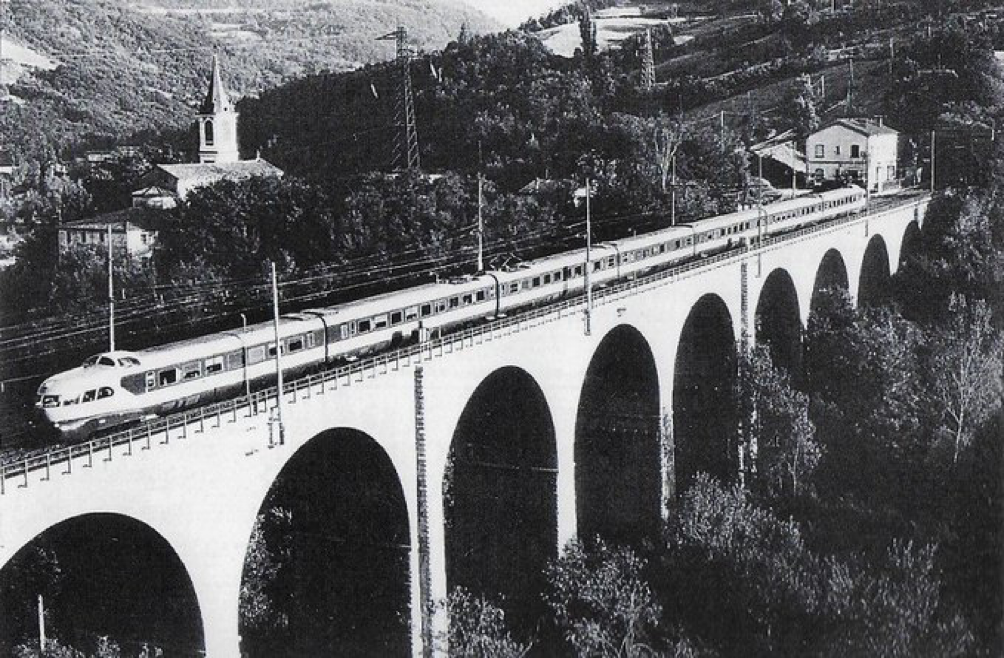

In 1939, the Polifemo “ETR” just stopped 3 minutes with no need for reversing.

The “gratuitous” Monte Adone tunnel, with its not negligible length of 7 km dug in very bad soil at high cost, epitomizes a change in the way rail infrastructure was planned, as seamless operations and time savings became so important to prevail over purely civil engineering ones.

-end-

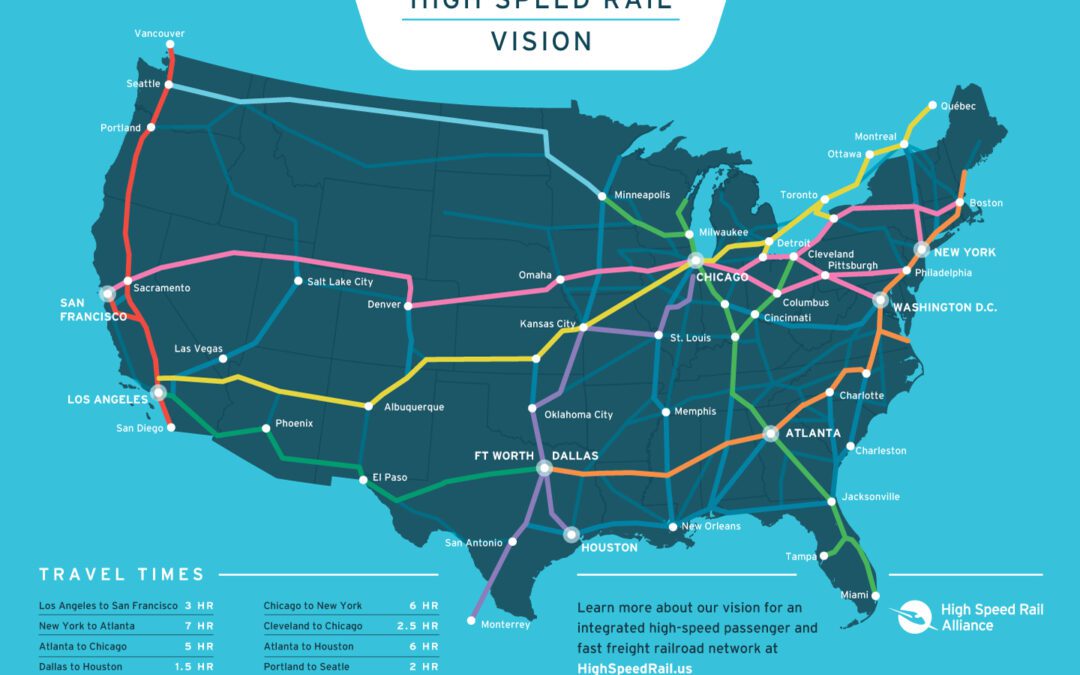

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!