Traveling last Friday through Iowa and Illinois, an eastbound Amtrak California Zephyr showed little or no sign of being affected by the CrowdStrike glitch and the cascading computer outages that followed. A morning announcement advised travelers that the café car...

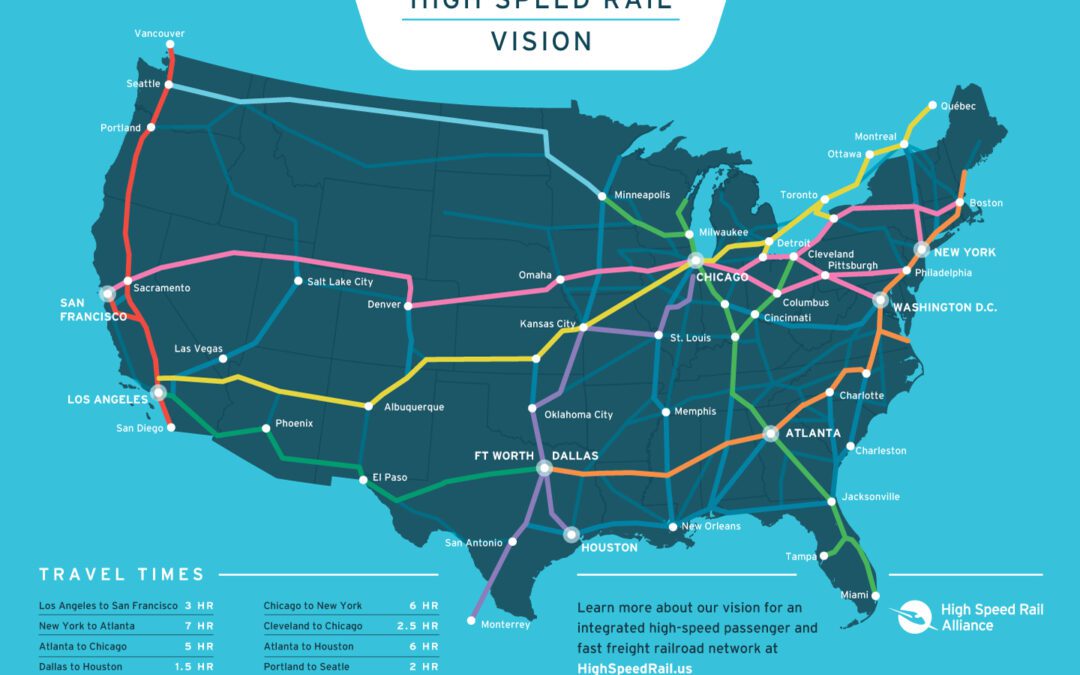

Building high-speed rail with the Phased Network Approach requires that we change some of the long-standing policy assumptions that have hampered passenger rail in the United States.

Today, high-speed rail and conventional passenger rail are seen as two separate things. Instead, we should think of high-speed rail as an evolution of the same infrastructure and practices that have helped railroads build our country for the last 200 years.

The financing and institutions needed to build segments of high-speed line are largely in place. Funding will come when there is a belief that enough people will benefit from the system. From a business perspective, it needs to be demonstrated that many people will ride the trains. From a political perspective, a diverse range of constituents—and their elected officals—need to see the value.

We need a new approach to planning that will represent more riders and constituents. Private railroads, as both the primary supplier and a powerful constituency, need a more productive financial partnership. And, we need new rolling stock to add new service and lower operating costs on existing service.

High-speed trains dramatically shorten travel time between stations. This effectively expands the areas that each station can serve.

Look Beyond City Pairs

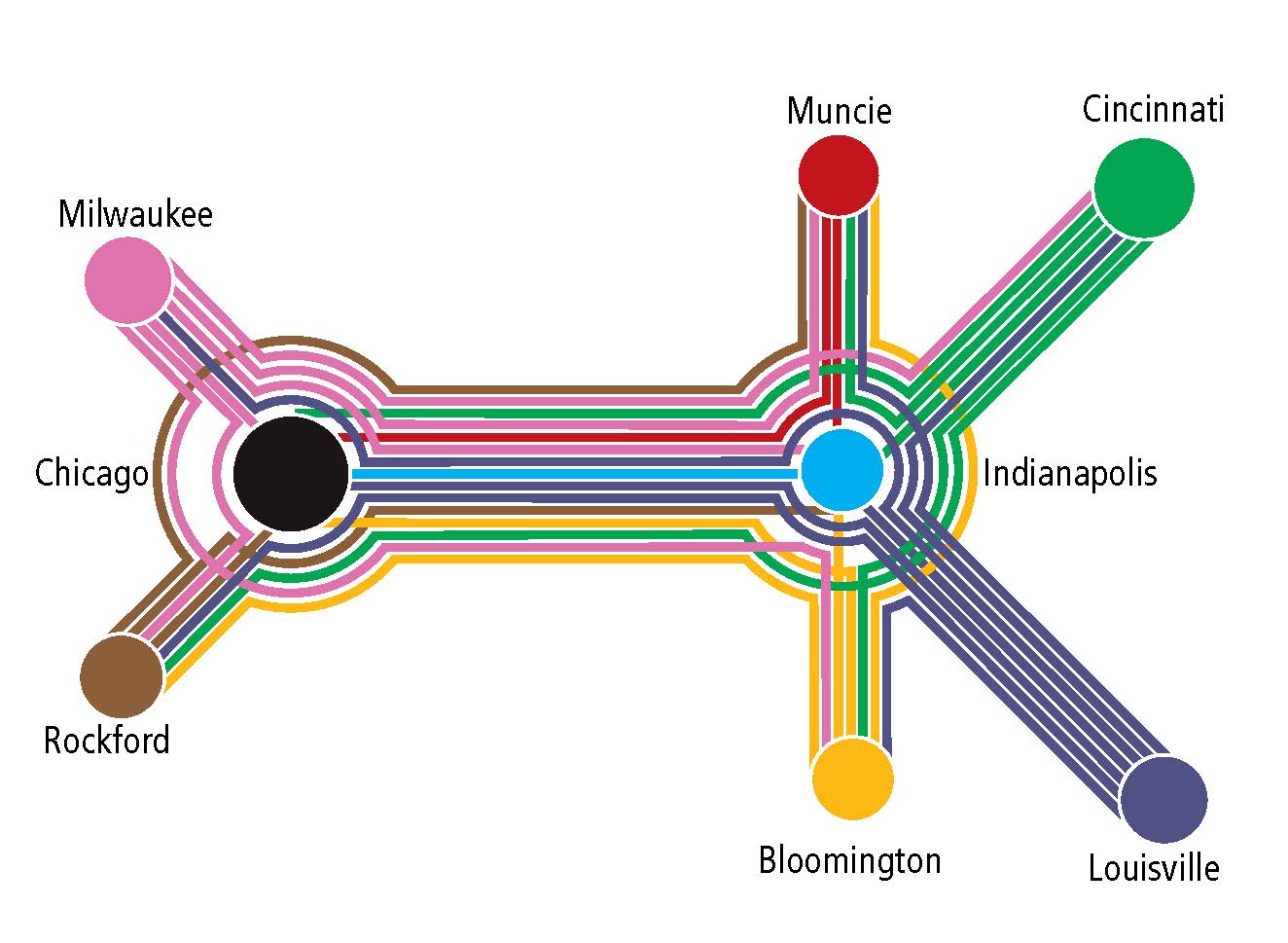

Today, planning, funding, and promotion of passenger rail service in the U.S. is preoccupied with pairs of cities. By restricting planning and modeling to two cities, or a corridor of cities along a single line, we ignore large markets of potential travelers that could be connecting from other parts of a network. Can we justify building a high-speed line between Chicago and Indianapolis for only the riders between those two cities? Probably. But once we include travelers from Milwaukee and Kalamazoo passing through Chicago and Indy to destinations like Cincinnati and Louisville, we get a critical mass of riders, political support, and funding.

Plan for interconnected networks instead of single routes

Transportation planners at all levels need to change their planning approaches and look at broad networks, rather than individual routes. This comprehensive view is necessary to serve as many people as possible on an interconnected network of new high-speed lines, existing branch lines and other modes like buses and ride share.

This limited thinking stems from established planning practices surrounding the dominant transportation systems in the U.S.: highways and air travel. These practices are focused on facilities—an individual stretch of road, or a single airport—with little attention to the broader network. While there may be detailed traffic counts for each segment, there is little to no information on where people are traveling to and why. Planning models assume that demand will continue to grow and that funds will be available for construction. These models often conveniently forget to account for the ongoing maintenance costs.

As a result, there is no precedent and little incentive for transportation planners in the U.S. to think about passenger rail systems as networks.

Look across service types and political boundaries

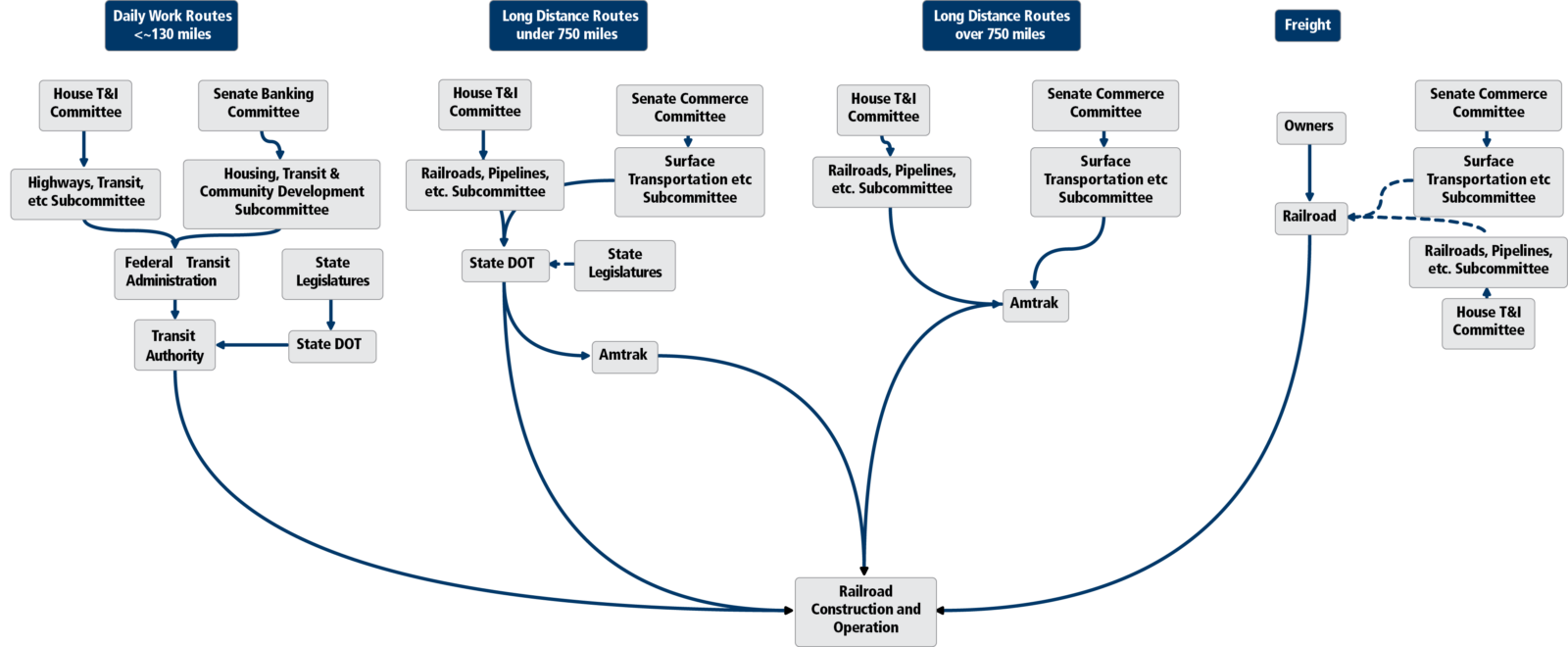

Planning and funding our railroad network through a snarl of disconnected committees and agencies makes it difficult to build the broad-based constituency needed to properly invest in high-speed rail. Where we should be combining markets we are instead splintering them.

American railroad planning is split between four types of service: daily work commutes, intercity trips under 750 miles, intercity trips over 750 miles, and freight. Even though the lines between these types of passengers are blurry, and these trains share the same track, the planning and funding for each happens separately.

With this division, the demand models used in planning often ignore the multiple types of riders a single train may serve: people may ride a commuter train for non-work purposes, while others commute on longer-distance regional trains. They also assume conservative ridership growth and thus limited available funding.

The Federal Railroad Administration has taken a first step in the right direction by leading multi-state planning sessions in four regions, including the Midwest.

CrossRail Chicago, which involves multiple markets, agencies and funding streams, would be an ideal test case for the Midwest.

California has created its first regional master plan, which should serve as a template.

Railroad planning in the United States is split among a snarl of disconnected committees and agencies that makes it difficult to build the broad-based constituency needed to properly invest in high-speed rail.

Change the relationship between states, Amtrak and private railroads

Unlike Europe and Asia, most of the rail infrastructure in the U.S. is privately owned. Amtrak, a quasi-government entity, and publicly-owned commuter railroads must negotiate with privately-owned railroads for use of their lines. Current policies and incentives have encouraged the railroads to reduce track capacity to its barest minimum. Most lines longer have sufficient track capacity to operate frequent passenger trains at competitive speeds.

Even with new, publicly-owned high-speed lines, achieving broad network coverage will require extensive use of private freight lines. We need a new arrangement between governments and railroads that gives railroads incentives to build and maintain passenger-grade trackage and to be proactive with potential service improvements that could increase passenger rail market share. The new bargain should persuade railroads to become advocates for increased government funding, just as highway contractors lobby strenuously for public investment in roads.

We need new policies that make operating passenger trains profitable for the railroads so that they will invest in the infrastructure needed to run them.

There are several strategies, many of which have been proven successful on individual routes in various states:

- Increase the rate per train mile

- Give the host railroad a share of the revenue increase

- Make incentive payments route-specific

- Reduce property taxes on railroads hosting passenger service

- Provide direct capital support for track work

- Provide more support for highway grade crossing separations

- Employ a dedicated track maintenance gang

- Use the right type of train equipment and keep station stops short

Read about these strategies in more detail.

Use modern train equipment

A train’s locomotives and coaches affect every aspect of service delivery: travel time, safety, operating costs, ridership and revenue. U.S. passenger trains have not changed much since the 1950s. Meanwhile, train designs have evolved in other parts of the world.

The United States needs to learn from overseas experience and update its passenger train fleet to modern equipment that can deliver high performance not only on dedicated high-speed track, but also on existing and sometimes rough freight track. That would include all trains, not just ultra-fast trains running exclusively on high-speed lines. Shared-use routes would be better served by modern equipment that can help reduce travel time.

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!