Traveling last Friday through Iowa and Illinois, an eastbound Amtrak California Zephyr showed little or no sign of being affected by the CrowdStrike glitch and the cascading computer outages that followed. A morning announcement advised travelers that the café car...

Substantially revised on 1/25/21

The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated ridership on passenger trains and public transit systems. Yet the current turmoil could also fundamentally shift the nation’s transportation paradigm. By highlighting the urgent need for that shift—and by incentivizing big investments in trains—it could initiate a new era of innovation and sustainable growth in the U.S. economy.

Here’s why, in three paradoxes:

Paradox 1. Commuting will likely become less common in the post-pandemic world as remote working gains wider acceptance and Americans are less tied to the cities where their companies have offices.

This shift—the Great Spacing, let’s call it—is a boon for small and mid-sized cities. NPR recently reported that Burlington (VT) has become a haven for tech workers from all over the country, and the population is growing in mid-sized cities like Little Rock, Louisville and Knoxville.

Some version of this model appeals to many workers, clearly. One survey found that about two-thirds of tech and finance professionals in New York, San Francisco and Seattle would move if they could permanently work from home.

Yet, even as there’s a growing disconnect between where people live and where they work, commuting to the office will remain a fact of work life for many professionals. It’s just that there will be less of it as people work from home one or two days each week.

Paradoxically, though, less overall commuting will increase the importance of first-rate passenger trains and public transit. That’s because their role in building the U.S. economy will expand as public transit (in particular) shifts away from being primarily a resource for low-income workers and becomes an essential amenity for everyone. Specifically, trains will allow professionals to easily check in regularly—in person—with the company headquarters or regional offices.

To understand why that’s so important, consider the paradox of cities at this moment.

Paradox 2. The Great Spacing means that, as professional workers become less tied to their offices, they’ll move away from big cities. Yet major urban centers and in-office work will remain vitally important because of the power of “clustering” and “collisions”—two of the great drivers of the U.S. economy.

“Clustering” means the concentration of skilled workers and creative talent in dense environments, which leads to virtuous cycles of innovation and productivity. Doubling the population of a city, according to one study, increases its productivity by an average of 130 percent.

What’s the connection between clustering and productivity?

When people and businesses cluster in a particular place, there are more face-to-face interactions—especially random interactions. And these so-called “collisions” spark creativity. As two analysts with McKinsey write, the “collision of ideas and perspectives fosters the emergence of unconventional collaboration and new solutions to tough challenges.”

That’s why companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook are moving forward with plans to increase their presence in New York. They could locate nearly anywhere at lower costs—as Amazon showed with its “competition” to build a second headquarters in 2018. In the end, none of the incentives offered by other cities compared with the benefits of locating in a thriving hub of innovation and creativity.

So, even as the Great Spacing pulls workers away from major urban centers—toward small and mid-sized cities with appealing amenities and affordable housing—the clustering and collisions that only happen in major urban centers—and in office spaces—will continue to drive innovation and productivity in the U.S. economy.

In short, the Great Spacing is pushing us toward a model in which choosing a place to live is less about proximity to work and more about the livability of a town or city. Yet the “synergies” generated in dense urban spaces, and in well-designed workplaces, remain critically important to success in business.

And that’s why it’s critical to have good trains that link small and mid-sized cities to major urban centers.

Paradox 3. Since many professionals, in particular, will split their time between working at home and working in a distant office, there will be fewer commuter trips. Yet the quality of the commute will be a key factor in a city’s—and a region’s—livability. “Quality” means the duration of the commute, how much it costs, and the stress it creates. On each of these counts, first-rate public transit and passenger trains solve many of the challenges we face.

Consider the case of Kalamazoo (MI), a city of about 100,000 people located about halfway between Chicago and Detroit. It’s well known for its high quality of life and the Kalamazoo Promise—a scholarship program that pays the full tuition to state universities for graduates of the city’s public high schools. From Kalamazoo, it’s roughly 150 miles to both Chicago and Detroit. That’s a 2.5-hour drive; it can easily be more, depending on traffic. So it may be possible to work remotely in Kalamazoo for a company in Chicago or Detroit—but the check in trips by car would be expensive, stressful, and a huge time waster.

Fast, frequent, and affordable trains change the calculus completely. If the tracks were properly upgraded, a worker could catch a train in Kalamazoo and be in Detroit or Chicago in under two hours—time that could be used to work or relax rather than focusing on the road.

Chicago and Detroit aren’t the only options. Fast, frequent trains would make Lansing, Ann Arbor, Grand Rapids—and dozens of other small and mid-sized cities throughout the region—an easy commute from Kalamazoo.

The same is true for towns and cities all along the line. Hourly trains from Chicago to Detroit would double as a commuter service between Ann Arbor and Detroit, for example. Or between Niles and Battle Creek. Or between any combination of those and many other stops.

It isn’t just about commuters, though. Trains have a powerful impact across a whole economy. Fast, frequent trains would drive an increase in tourism from Chicago—and more day trips by in-staters. And they would lay the groundwork for Michigan to become the heart of a high-speed rail corridor extending from Chicago to Toronto—anchored by the high-tech innovators clustering in Ann Arbor and Detroit. Find the Alliance’s vision for Michigan here.

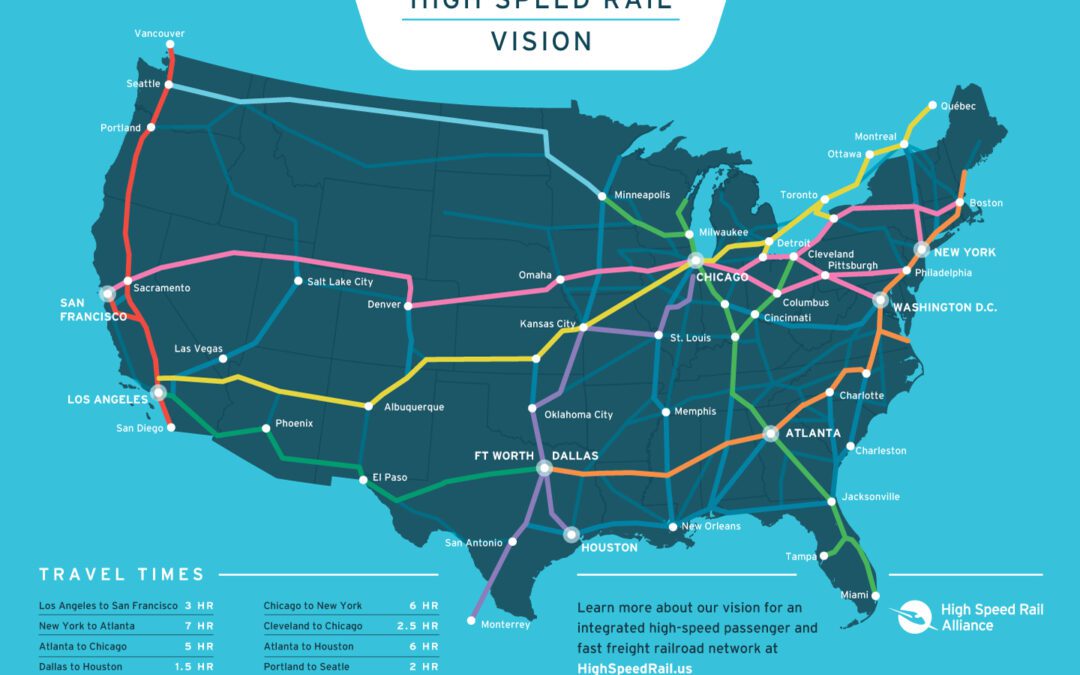

There are plenty of similar possibilities across the U.S.—livable towns and cities that would thrive by being tightly connected to major urban centers with first-rate trains.

Nothing is certain, of course. Everything depends on creating a vision and finding the political will to push it forward. But we can see clearly the possibilities now. As the Great Spacing proceeds, it’s time to get moving.

The Latest from HSRA

Our Latest Blog Posts

Check out the latest news, updates, and high speed rail insights from our blog!